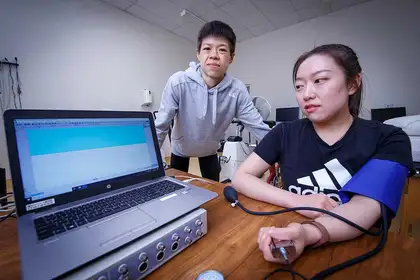

PhD student Beverly Tan has been testing healthy women for her project over the past two years at Massey’s Manawatū campus.

New research from Massey University’s College of Health is testing whether a woman’s level of hydration could be affecting her tolerance and sensitivity to pain, and if it is related to her menstrual cycle.

In New Zealand, one in five adults report experiencing chronic pain lasting more than three months at an annual cost to our society that exceeds that for diabetes and dementia.

Compared to men, women report more frequent, persistent and widespread pain with substantially more women suffering from clinical pain conditions.

Dr Toby Mündel, an associate professor in the School of Sport, Exercise and Nutrition, led a previous study that found that the more dehydrated men became, the more intense their feelings of pain.

Now PhD student Beverly Tan wants to know whether this is the same for women, and whether this effect might be greater at certain times of the menstrual cycle.

“We know that for 20-50 per cent of women hypohydration, a state of reduced body water content, is a common occurrence. We also know that due to the natural changes in female hormones, like oestrogen and progesterone, how the female body regulates body water and thirst changes across the menstrual cycle,” says Miss Tan.

So, for the past two years Beverly has had healthy women visiting Massey’s Manawatū campus after they consumed their usual amount of fluids or after they refrained from fluids for 24 hours.

On both visits they performed 25 handgrip exercises with a cuff around their arm stopping the blood supply from leaving, with the time before they asked for the cuff to be released used to measure tolerance.

Miss Tan says this method is thought to be the most clinically relevant, as the deep and aching pain produced better replicates then the pain experienced in many clinical pain syndromes.

“Both visits are arranged in the first week (early follicular) and then again in the third week (mid-luteal) of their menstrual cycle, weeks that are very different in terms of their hormonal make-up i.e. low vs high concentrations.”

Miss Tan is yet to complete her data analysis before submitting her thesis, but the preliminary results indicate that when women were hypohydrated their sensitivity to pain was greater whilst their tolerance to pain was reduced.

She says, “the possibility of recommending people avoid dehydration and encourage regular fluid consumption to minimise pain and allow other treatments such as analgesics or cognitive behaviour therapy to be effective is a simple yet powerful and effective outcome.”

Miss Tan’s research is a collaboration with Massey staff members from the School of Psychology and the Universiti Sains Malaysia.

You can read the full paper published in Frontiers in Physiology

You can read the full paper published in Psychophysiology