Published this week in Ecology and Evolution, the study is a collaboration between Massey and iwi, in partnership with the University of Wollongong, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, the National Marine Mammal Foundation and the Epigenetic Clock Development Foundation.

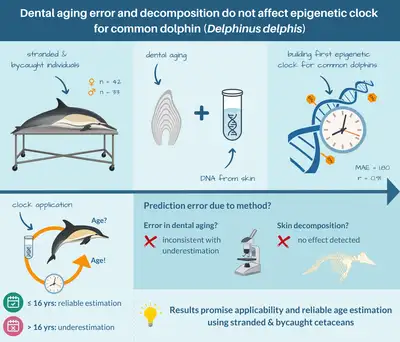

The research answers a long-standing question about dolphin ageing and resolves concern over whether teeth from deceased dolphins can reliably be used to develop DNA-based ‘age clocks’. The research confirms that they can, and that the genetic clocks work even when built from post-mortem samples.

The team analysed 75 common dolphins that had stranded or been accidentally caught in fishing gear around Aotearoa New Zealand between 2000 and 2023. For each dolphin, they estimated age by counting growth layers in its teeth – much like reading tree rings – and compared these with patterns in the animal’s DNA. These DNA patterns, called epigenetic markers, change predictably as animals grow older.

Common dolphins are one of the most widespread dolphin species globally but are increasingly threatened by accidental capture in fishing nets, as well as pollution and habitat degradation.

By combining the tooth and DNA data, the researchers built the first molecular “epigenetic clock” for common dolphins. This clock provides a practical way to estimate how long common dolphins live, when they reproduce and how many young survive – information that is critical for tracking population changes early and acting before declines become irreversible.

They also tested how accurate the clock was for older animals and whether natural decomposition of skin samples affected the results.

Epigenetic clocks are a growing tool in wildlife science. They estimate an animal’s age using chemical changes in DNA from small tissue samples, without needing to remove teeth or relying on invasive methods. However, to build these clocks, scientists need samples from animals of known age. For many long-lived marine mammals, such known-age records from wild or captive populations are limited.

This study shows that teeth from deceased dolphins can reliably underpin DNA-based age clocks, opening new possibilities for understanding and protecting wild populations.

Until now, scientists weren’t sure whether the limits of tooth ageing—especially in older animals— might reduce the accuracy of DNA-based age estimates. There were also concerns that DNA from dead animals might degrade too much to be useful.

However, the team found no evidence that decomposition or age-related limitations affected the clock’s reliability.

“Our results show that dolphins aged from teeth after death still provide reliable data to build epigenetic clocks,” Lead author Evi Hanninger says.

She says the research also highlights the value of existing tooth collections to develop molecular clocks for other dolphin species.

“For many dolphin and whale species, tooth records from stranded or accidentally caught animals are often the only source of age information. Knowing that these samples can reliably underpin DNA clocks means we can extend this approach far beyond a single species.”

Senior author Professor Karen Stockin says the findings have direct implications for conservation.

“Once a clock is built, we can estimate the ages from wild dolphins using small skin samples collected with biopsy darts. That means we can finally assess age structure, survival and reproduction in living common dolphin populations – crucial information for managing their future.”

Read the paper: Dental Ageing Offers New Insights Into the First Epigenetic Clock for Common Dolphins (Delphinus delphis)

Related news

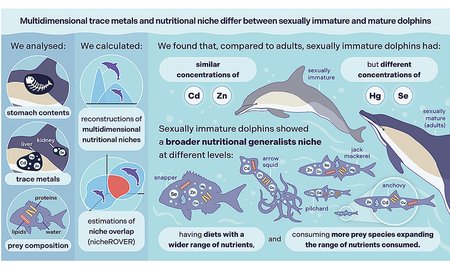

Study reveals how dolphin maturity affects the ingestion of dietary nutrients and trace elements

The Massey-led study assessed common dolphins over a three-year period, resulting in some surprising insights.

New research calls for consistent guidance during euthanasia of stranded cetaceans

New research reviewing the standard operating procedures for euthanasia of stranded cetaceans across Australasia has highlighted the need for more detailed guidance and consistency.

Freezer with a porpoise

Associate Professor Karen Stockin and her team from the Cetacean Ecology Research Group (CERG) at Massey University were relieved to take delivery of their new 20ft walk in freezer last week to safely store the largest marine mammal tissue archive in the southern hemisphere.