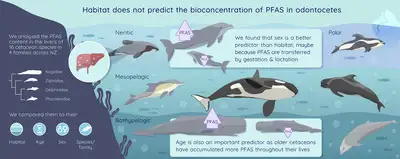

Led by Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University, the study analysed tissues from 127 toothed whales and dolphins across four families found in Aotearoa New Zealand. The aim was to understand how an animal’s habitat affects the build-up of PFAS in its body.

Researchers measured PFAS concentrations in 16 species ranging from inshore coastal dolphins, like bottlenose dolphins, to offshore deep-diving species such as sperm whales. For eight of those species, including Hector’s dolphin and three species of beaked whales, this was the first time PFAS levels had been assessed anywhere in the world.

In each species and family, the team looked at how levels of these ‘forever chemicals’ varied according to species, sex, age and the ocean habitats where the animals mainly feed.

PFAS are human-made chemicals – over 14,000 compounds – found in everyday products like non-stick cookware, food packaging, clothing, cleaning supplies and personal care items. Some of these chemicals can attach to proteins in animals and build up through the food chain, which can affect the immune system, hormones and reproduction. This means PFAS pose risks not only to individual animals but also to entire populations.

PFAS enter the ocean through a range of sources, including urban and farm runoff, industrial and manufacturing discharges, wastewater treatment plants and even from the air. Because these chemicals do not break down naturally, the oceans are their final destination, making their build-up in marine food chains a critical concern.

This research is a trans-Tasman collaboration involving Massey University, the University of Wollongong, University of Technology Sydney, the Bioeconomy Science Institute and the University of Auckland. It is the first of its kind to measure PFAS burden across a wide range of marine species, at a single point in time, and across different ocean habitats.

Study lead and Massey University Professor Karen Stockin says that until now, it was unclear how PFAS levels reflected the habitats of species.

“Scientists historically assumed that deep-water species, like sperm whales, would be less affected by PFAS than shallow coastal species, such as Hector’s dolphins. But the reality is not so simple.”

Published in the international journal Science of the Total Environment, the study found that habitat is actually a poor predictor of PFAS levels in marine mammal tissues: there is no ocean environment free from these ‘forever chemicals’.

For example, species feeding midwater, like false killer whales and common dolphins, were just as exposed to PFAS as coastal Māui dolphins or deep-diving species like beaked whales.

Louis Tremblay, an ecotoxicologist on the research team from the Bioeconomy Science Institute, says the working hypothesis was that PFAS entered animals mainly through the food chain, but the results have shown multiple sources, including chemicals in the water itself.

“This confirms that PFAS are everywhere in the marine environment, and we still don’t fully understand their impact, especially on predator species like whales and dolphins.”

Professor Stockin adds that the models indicate habitat plays only a minor role in PFAS accumulation in these animals.

“Instead, sex and body length – which reflects age – were stronger predictors. This suggests PFAS can be passed from mothers to calves, and older animals accumulate more over their lifetime.”

Research Leader of the Biogeography, Ecology and Modelling Lab at the University of Technology Sydney and Research Scientist at the Australian Museum Dr Frédérik Saltré adds:

“This suggests that even offshore and deep-diving species, which might seem isolated from humans, are exposed to similar levels of PFAS. This shows how widespread pollution is, and how it adds to climate-related stressors, threatening marine biodiversity.”

Environmental and Chemical Biotechnologist in the Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering at the University of Auckland Dr Shan Yi says the study provides evidence of PFAS across many whale and dolphin species, but the health effects remain largely unknown.

“Developing models to link exposure to specific health outcomes will be critical for assessing risks to both individual animals and populations.”

Read the paper: No place to hide: Marine habitat does not determine per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in odontocetes - ScienceDirect

Related news

New molecular ‘age clock’ for common dolphins a game changer for conservation

Researchers have developed the first DNA-based method to estimate the age of common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) using samples collected from animals that were stranded or accidentally caught.

Microplastics revealed in New Zealand marine mammals for the first time

Scientists have found microplastics in all New Zealand dolphins they examined, a new study has revealed.

New research reveals emerging environmental contaminants of concern in NZ dolphins

Scientists have revealed emerging environmental contaminants of concern within New Zealand dolphins, with similar pollution levels to Japan.