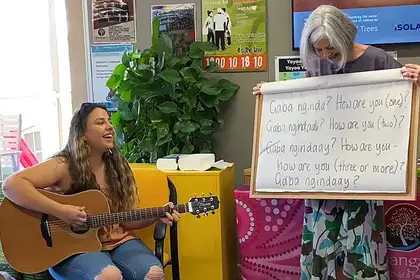

Dr Hilary Smith (right) at the book launch in Gunnedah, NSW, last week with Gamilaraay singer, Loren Ryan.

A New Zealand linguist has launched a series of children’s books she co-wrote in Gamilaraay – an endangered Aboriginal language she is working to revive using mostly digital technology in collaboration with a community in New South Wales, Australia.

Dr Hilary Smith, an honorary research fellow at Massey University’s School of Humanities, has been involved in extensive community language work in the small town of Gunnedah near Tamworth for four years. Last week five children’s books – the first bilingual early readers in the language – were launched there.

Dr Smith says the Gamilaraay revival is at the early stages. There are no fluent speakers to assist with developing teaching materials as the last died in the 1970s. It is one of many Aboriginal languages currently being revitalised with just 13 from the 250 once spoken by Aboriginal peoples still in use.

The books are part of the Yaama Gamilaraay! project funded through the New South Wales Department of Education’s Ninganah No More programme, and were produced with the support of Library For All Australia. The response has been very positive, she says, and are a great way to mark the end of the United Nation’s International Year of Indigenous Languages.

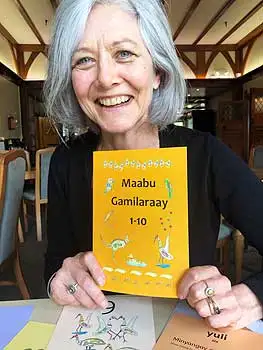

The stories of Gamilaraay Yawa-la (Speak Gamilaraay) are based around everyday interests and activities identified by the community and illustrated with images by local photographers and artists. Dr Smith has also created colourful counting flash cards illustrated in traditional designs, as well as a phonetic pronunciation chart, online dictionary, and produced teaching videos and songs showcasing the Gamilaraay language for YouTube.

Using digital technology to revive an ancient language, much of her work is shown on Yaama Gamilaraay! – a website she has been developing at the Winanga-Li Aboriginal Child and Family Centre in Gunnedah. She has also developed Word of the Week for YouTube, which is shared on Winanga-Li Facebook, Instagram and intranet for staff and families, as well as the wider Gamilaraay language community Facebook page.

Dr Hilary Smith with one of her books in Gamilaraary.

Can language revival heal intergenerational trauma?

The project has enabled Dr Smith to her harness her expertise in social psychology, applied linguistics and international and community development through her earlier experiences with Volunteer Service Abroad – Te Tūao Tāwāhi. She also draws on her experience teaching English as a Second Language in Laos, Tonga and Papua New Guinea, and subsequent work in New Zealand.

Mindful of the intergenerational trauma affecting generations of Aboriginal peoples as a result of an estimated 250-plus massacres killing thousands between European settlement in 1788 and the mid-20th century, she says there is the potential for a healing impact through language revival. “There is an increasing body of research and anecdotal evidence of a link between wellbeing and language revival,” she says. She has been working with colleagues at the Australian National University to review the evidence for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Acknowledging the need for cultural relevance as the core of effective, meaningful language learning tools, Dr Smith has developed a framework based on the Gamilaraay idea of bina (ear).

“In many Aboriginal languages, the ear is the centre of cognition rather than heart. It is related to words to do with listening, understanding, knowing, respecting and for knowledge – all come from the word for ear.”

Her work is part of a series of Gamilaraay language projects set up in partnership with the ANU’s School of Literature Languages and Linguistics, where she is working with linguist Dr John Giacon, the leading descriptive linguist working on Gamilaraay.

He had been invited to work with Winanga-Li around the time Dr Smith went to the ANU and became keen to learn an Australian language. When she met Winanga-Li staff she learnt of their hunger to revive Gamilaraay.

She has been interviewing people who recall elders speaking the language, which was forbidden by authorities. Echoing the experiences of speakers of te reo Māori in the early to mid-1900s, in Australia more draconian policies meant that children known as the “stolen generations” were removed from school and from their families for speaking their own language, Dr Smith explains.

Mahalia Pryor (the subject of one of the books) with her Nan, Leanne Pryor.

The colour purple

She says one of the most exciting and challenging aspects of working in language revival is “working out what to do when there is no word for what we need”.

There was no word for the colour purple, so she consulted with her Gamilaraary colleagues and looked to nature. “I am particularly excited about bibubibu, which is the first word to be proposed from my studies. I had never before heard of a dillon bush [which has purple berries called bibu], but it sounded perfect! So bibubibu was our suggestion for ‘purple’.”

To see more detail for one of these projects see http://winanga-li.org.au/index.php/yaama-gamilaraay/

Read more on Dr Smith’s blog about finding the word for the colour purple in the Gamilaraay language here: https://languagealive.blog/2018/12/11/the-colour-purple/

The Speak Gamilaraay YouTube channel is https://www.youtube.com/speakgamilaraay