New Zealand’s mainstay drug law turned 50 this year – yet we still don’t have a clear, comprehensive picture of the social harms different drugs pose.

When the Misuse of Drugs Act was introduced in 1975, it codified a set of prohibitions shaped not only by evidence of social harm, but also by the politics and anxieties of the time.

Drug bans have historically reflected a mix of genuine harms, moral panic, political expediency, prevailing attitudes, prejudice against minority groups and industry influence.

More recently, scheduling decisions have been influenced by media coverage, public concern, piecemeal social statistics and the views of academics and agencies.

A common proxy for judging a drug’s harm is the extent to which it is linked to dependency.

Several self-reported screening tools are used to assess dependency – but these typically bring a psychological framing to an issue that we know is multi-dimensional, with societal impacts that reach beyond the drug user.

Some progress has been made in developing broader harm rankings for different substances, but such assessments rely on small, select panels with narrowly focused expertise.

While there are a handful of social harm indexes of drug use, these also come with significant gaps.

To help address such limitations, we developed the Substance Outcome Harm Index (SO_HI) which is grounded in the idea that people who use drugs can offer valuable, experience-based insight.

Although its methodology is still being developed, our early findings provide new insights that challenge common beliefs about drug use and harm.

What our new index revealed

Our SO_HI index draws on data from more than 4,800 anonymous respondents to the 2025 New Zealand Drug Trends Survey, whose large sample broadly mirrors the wider population.

Respondents were first asked whether, in the past six months, they had experienced harm from alcohol or drug use in any of 12 identified life “dimensions”. These range from physical and mental health to relationships, personal safety, work/study performance, parenting and care giving, violence and money.

The harms described are largely acute problems to make it easier for substance users to link them to their recent alcohol and drug use. Some substances, such as tobacco, are also responsible for long term chronic illnesses and these harms are not well captured in our index.

For each area where harm was reported, respondents were shown short descriptions of four escalating levels of seriousness and asked to choose the highest they had experienced.

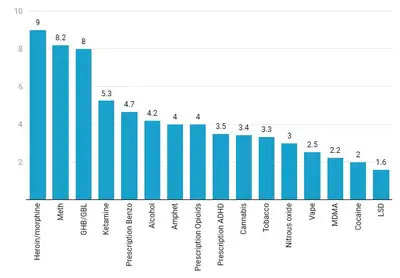

Score showing the mean risk of harm by drug type

This graph shows mean risk-of-harm scores for each substance on a scale which combines 12 drug-related harm "dimensions" and four levels of severity.

Interestingly, nearly two thirds of respondents (63.1%) did not report any negative outcomes from drug use across any of the dimensions.

The drug-related problems most commonly reported were mental health issues (19.0%), money problems (18.2%), physical health impacts (14.6%), and relationship difficulties (14.3%).

Fewer participants reported work or study problems (10.5%), unsafe driving (6.7%), or personal safety concerns (6.7%). Only a small proportion (3.1%) reported legal issues linked to their substance use.

When asked which substances were responsible, 60% of respondents identified a single drug (59.7%), a quarter identified two (26.3%), and around 9% identified three.

On our index, heroin/morphine, methamphetamine and GHB/GBL (also known as fantasy, liquid ecstasy or G) carried the highest cumulative mean harm scores across the 12 dimensions.

At the other end of the scale, LSD had the lowest harm mean score, followed by cocaine and MDMA (ecstasy) – with the latter scoring only a fraction of methamphetamine’s harm level.

These scores reflect the current patterns of use in New Zealand and will differ across countries depending on prevalence, price and availability.

For example, cocaine’s low score likely reflects the low availability and low frequency of use in New Zealand. In our sample, 71% of cocaine users had used it only once or twice in the past six months and 21% used it monthly.

Alcohol ranked sixth in our index, behind heroin, methamphetamine and GHB.

This differs from some published international rankings that place alcohol at the top. However, our index measures individual risk of harm, not total societal harm, which would account for prevalence of use.

Some harm assessments were also based on relatively small numbers of respondents naming a drug as responsible for harm.

Where our research goes next

Our preliminary findings illustrate the value of engaging with drug users to assess and compare the risk of harm of different drug types to inform policy response and health service resourcing.

The risk-of-harm scores can also be broken down for demographic groups that may be more vulnerable to drug harm – such as young people or those with mental health issues – and for ethnicities often poorly served by health services, including Māori and Pacific peoples.

Our questions could also be posed to specific groups, such as heroin users, to improve estimates for substances that are rarely used.

We are now developing a method for weighting different harm attributes and severity levels. For instance, some people may consider harms related to parenting more serious than those related to property crime or poor work performance.

We are also validating our findings against other harm measures and assessment tools, and further refinement will be coming.

There is a need to account for harm related to poly-drug use, given that 40% of our sample named more than one substance as responsible for their problems.

Applying our index in other countries, where drug availability and patterns of problematic use differ, will also be important for enabling robust international comparisons.

Dr Chris Wilkins is a Professor of Policy and Health, Dr Marta Rychert is an Associate Professor in Drug Policy and Health Law, Dr Robin van der Sanden is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Public Health at the SHORE & Whāriki Research Centre and Dr Jose S. Romeo is a Senior Research Officer and Statistician.

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Related news

Survey shows social media transforms drug buying as gangs rule meth in key regions

The 2024 New Zealand Drug Trends Survey highlights shifting dynamics in the country’s drug landscape, with regional gang dominance and digital platforms reshaping how drugs are bought and sold.

Survey shows one-third of medical cannabis users now have a prescription for legal prescribed cannabis products

Findings from the latest New Zealand Drugs Trends Survey (NZDTS) reveal progress with the uptake of the Medicinal Cannabis Scheme.

One in four survey respondents used pharmaceuticals for recreational or non-medical reasons

The second set of findings from the 2024 New Zealand Drugs Trends Survey (NZDTS) sheds light on emerging trends in the non-medical use of pharmaceuticals and the therapeutic use of psychedelics.

Latest NZ Drug Trends Survey shows growing influence of digital and synthetic drug markets

The first findings from the 2024 New Zealand Drug Trends Survey (NZDTS) show a decline in the price of meth, increasing cocaine use and availability and an increased availability of psychedelics.