Te Rau Karamu marae on the Wellington campus.

A couple of years ago a young wāhine Māori – let’s call her Rangimarie, although that is not her name – sidled up after the first lecture of a course I teach and told me that her first language was te reo Māori. Her English was ok, she said, but it was definitely a second language. We spoke awhile (she in her second language and me in my first), and then she strolled off to her next class.

Rangimarie did not have an easy time of it at uni. She was treated differently to the vast majority of students: she did not receive instruction in her mother tongue, she was unable to have her work marked in her first language, and while most people’s tattoos go unremarked these days, Rangimarie was occasionally abused for the moko kaue she carried. She got there, in the end, but it was hard going.

I thought of Rangimarie when I read of the member’s bill drafted by ACT MP Dr Parmjeet Parmar, intended to ‘ensure universities do not allocate resources, benefits or opportunities based on race (sic).’ In particular, I thought of the room designated as a space for Māori students at my university, which Rangimarie spent time in, and which Dr Parmar seems to have taken against.

I don’t know how much Dr Parmar knows about universities. I’ve worked in them for over 30 years, during which time I’ve learned a thing or two. One is that nobody is excluded from the Māori spaces on my campus. Drop in (as I and other non-Māori routinely do) and you’re warmly welcomed – usually with more food than is good for you.

A second thing I’ve learned is that Māori students sometimes need to be able to go to parts of the campus where they can (a) be themselves; (b) speak their language without being abused or looked at funny; (c) not be constantly asked by non-Māori how Māori feel about the issue du jour; and (d) not have to put up with the racism stirred up by some of the policies introduced by the Government of which Dr Parmar’s party is a member. These days, the spaces she would like to get rid of are places of refuge for students like Rangimarie.

A third thing that has recently dawned on me is that the ACT Party has a poor grasp of liberal democratic theory. ACT happily embraces equality of treatment but appears to be unfamiliar with the rest of the liberal canon. As an avowedly liberal party, it is especially surprising that Dr Parmar and her fellow travellers seem to be unacquainted with Sir Isaiah Berlin, whose distinction between negative freedom (the absence of obstacles or barriers) and positive freedom (the possibility of taking control over one’s life and realising one’s purposes) seems apposite. Sir Isaiah was big on pluralism, and I suspect he would defend both Rangimarie’s freedom to be Māori and also her right to freedom from those who would deny her that right. He is a towering figure in the liberal tradition, but somehow or other the ACT Party seems to have missed him.

This means ACT’s position on individual liberty is a little patchy. I may stand corrected but I assume that ACT’s insistence on equal rights for all individuals means ensuring people are free to be themselves. Treating people equally, then, must mean allowing them to be different: if I am free to be myself (Pākehā, English-language speaker, etc.) then so is my Māori student (Māori, te reo Māori-speaking, etc.). To argue that Rangimarie and other Māori students should be denied access to the small room in which they can be themselves is an illiberal position to take, not a liberal one. But I guess that is what you get when you only know half the recipe.

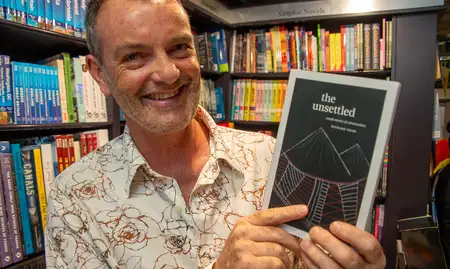

Professor Richard Shaw.

While I have learned some things, there are many I still do not understand. For a start, I don’t understand what motivates Dr Parmer’s proposed legislation. I assume it is a concern that the provision of Māori spaces on our campuses means someone else misses out on or is denied something. But what? I can see what Rangimarie gained from that Māori space, but can’t understand who loses out from its existence. Certainly not Pākehā students, for whom the rest of the entire campus comprises rooms, corridors, quads, libraries and lecture theatres where they get to be themselves: to speak their native language, see lots of others like them wandering about, and learn curriculum consistent with their worldviews (see: liberalism). How much space do we need? When is enough enough?

Universities – from their built environments to the course content they offer – are rooted in Western civilisation. I often forget that, because it is so obvious that it becomes invisible. Universities are wonderful places, but if we need to carve out spaces in which Māori and others can be themselves, so that our universities are better able to embrace other ways of knowing and seeing the world, whose individual liberties are impinged upon? Certainly not mine. Nor Dr Parmer’s, for that matter.

One final thing I do not understand is: To what problem is Dr Parmer’s bill the solution? There is no shortage of pressing material issues to hand: the climate crisis, the degradation of democracy, the end of the liberal international order, the cost of butter. Take your pick. I am fairly sure most people would not add the need to deny Māori students access to rooms in which they can be themselves to that list. I am also confident that most people would much prefer ACT spent scarce parliamentary time and resources on things that matter to us all, rather than on issues the party faithful seem fearful of.

Rangimarie moved across worlds, and my university was a better institution for her presence. More welcoming. More plural. Frankly, more interesting than it would otherwise have been. So, sure, by all means, let’s treat everyone equally. But that means making room for people to be themselves.

Professor Richard Shaw is a professor of politics in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. He is a regular commentator on political issues.

Related news

The Unsettled: Small stories of colonisation

Professor Richard Shaw’s latest book explores the historical and emotional territories of New Zealanders coming to terms with the ongoing aftermath of the New Zealand Wars.

Opinion: Let’s talk about equality – and the constitution

By Professor Richard Shaw