This opinion piece is the third of a five-part series on the intertwined webs of the far-right mobilised to attack communication and media studies pedagogy. This piece is written in solidarity with other communication and media studies academics, researchers, and practitioners who have been targeted by the far-right.

The far-right want to cancel communication and media studies. The entire discipline!

A platform titled The Centrist published the article, "Abolish communications and media studies (Karl du Fresne)", stating "Writer Karl du Fresne says abolishing the department of communications and media studies at every university will vastly ease the financial crisis of those unis while neutralising a key source of division in the culture wars."

The irrational rant would be comical if not for the violence the rhetoric promotes, the direct effects of which are experienced by academics in the public sphere. Increasingly, the far-right has launched attacks targeting academics and universities, both in digital and public spaces, resulting in violence on campus. For obvious reasons, its obsession with academics and journalists studying and covering misinformation and hate, have made carrying out research and sharing it publicly unsafe. Attend here to The Platform's targeting of AUT journalism academic, Dr Greg Treadwell for his public writing on harmful disinformation, and similarly du Fresne's targeting of The Disinformation Project’s Dr Sanjana Hattotuwa and Kate Hannah, and Radio New Zealand’s Susie Ferguson.

I personally have witnessed pile-on hate from far-right groups, including receiving death threats and rape threats. Academics across institutions in Aotearoa who have written to me in response to this series have shared the intimidation, threats and harassment they have experienced, resulting from similar attacks targeting them, documenting the chilling effects.

Du Fresne's article holds the entire discipline of communication and media studies responsible for the divisiveness in New Zealand society, accusing the discipline of stoking "culture wars."

The conspiracy theory debunked earlier is recycled:

"There seems to be no purpose to those studies other than to promote neo-Marxist theories about oppressive power structures, racism, misogyny, white supremacy, social and climate justice and decolonisation. The faculties are infested with zealots and activists with ideas inimical to values such as free speech. Not to mention, they’re useless studies in their own right. Cutting them will help shed weight."

Theories that challenge oppression, misogyny, and white supremacy, and seek to promote social justice, climate justice, and decolonisation are conspiracies. A racist version of this propaganda concocts Māori elite conspiracy to attack Kaupapa Māori theory and research practice. Topics that critically interrogate white supremacist power and control are conspiracies in this ideological universe, fuelled globally by the Trumpian attack on Critical Race Theory and the far-right's reactionary attack on tertiary education.

Far-right attacks on academic freedom

The call to dismantle the discipline of communication and media studies tars academics in the discipline as "zealots and activists with ideas inimical to values such as free speech."

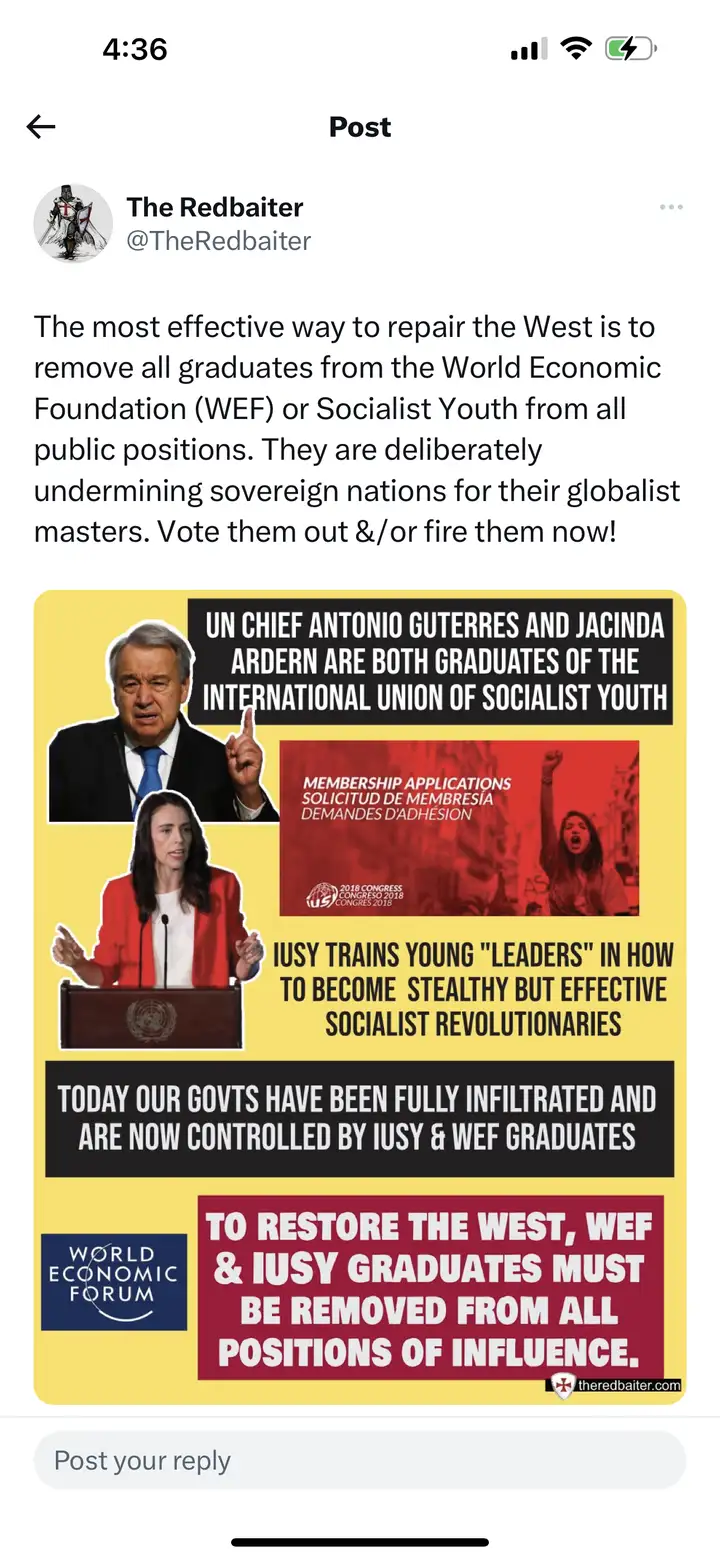

So, what is the far-right’s free speech? It is on one hand the unfettered right of white supremacists to spout hate targeting Indigenous communities, ethnic and religious minorities (including migrants, and especially Muslim migrants), and gender-diverse communities (particularly transphobia). On the other hand, communicative practices that empower those at the margins to resist white supremacy are portrayed as dangerous. Academics researching and studying practices of empowering the marginalised are radical elites conspiring to disrupt New Zealand society.

Elsewhere, du Fresne whimpers about the right of Christian lobbying organisation Family First to place its advertisements on mainstream media infrastructures, blaming these media organisations for colluding to suppress and participating in a conspiracy to silence speech.

What du Fresne seems to have a problem with are critical studies of entrenched white supremacist, settler colonial, patriarchal power and resistance to this power. Elsewhere, he laments the New Zealand he once knew is rapidly changing, almost becoming unrecognisable to him!

Critiques of "oppressive power structures, racism, misogyny, white supremacy," and ideas espousing "social and climate justice and decolonisation" are "ideas inimical to values such as free speech." Du Fresne’s problem is that entrenched forms of white supremacy are being challenged, brought about by the increasing participation of marginalised communities in naming oppressive practices, witnessing them, and resisting them. For white supremacists, free speech as a value is specifically organised to safeguard their right to spout hate while brazenly silencing the voices of marginalised communities who are the targets of hate.

Consider here the recycling of the neoliberal trope of utility to define academic freedom, suggesting that academic disciplines can have academic freedom to the extent they have utility. The framing of communication and media studies as useless, without any semblance of empirical evidence, shows his ignorance about what the discipline actually is. Contrast this vacuous claim with the empirical evidence pointing to the diverse career pathways offered by communication studies and the global demand for jobs with communication skills and training in communication (more on this in the last piece in this series).

Far-right and “cancel culture”

One of the key advocates for academic freedom put forth by The Free Speech Union wants to cancel a discipline and dismiss entire departments of academics while preaching about academic freedom.

The far-right has had a long history of targeting speech that threatens the status quo.

Consider the organising of the far-right in the United States to ban books such as Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut Jr; The Best Short Stories of Negro Writers, edited by Langston Hughes; Go Ask Alice by an anonymous author; Black Boy by Richard Wright; and Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver, mobilised since the 1970s. The National Coalition against Censorship in the US observes, "Books by Black authors are among the most frequently banned."

In the last seven years, with the global rise of white supremacy, rallied by Trump and his hate ecosystem, the far-right cancel culture is turbo-charged, mobilised through online networks.

This takes the form of organised attacks on libraries, curricula, and public programmes that are anti-racist and that seek to promote spaces for diverse voices at the margins.

Across Aotearoa, Rainbow Storytime events have been targeted by the far-right, framing the events as propaganda tools for brainwashing children and youth. Worse, the events are depicted by the far-right as grooming sessions, a narrative that perpetuates fear and violence directed at transgender women. In the current cycle of far-right hate, the targeting of transgender communities forms the rallying infrastructure for growing the hate movement.

Note here the far-right’s targeting of the transgender activist Shaneel Lal, and the actual acts of violence that have been directed at Shaneel. Also consider simultaneously the elaborate defense that du Fresne launches for the free speech rights of activist Posie Parker, aka Kellie-Jay Keen-Minshull, and the escalation of anti-transgender hate that was mobilised by Parker's recent visit to Aotearoa.

Observe the convergence with Trump's mobilisation of the term "cancel culture" in his July 2020 Independence Day speech, with the term being deployed to depict the resistance to white supremacy offered by marginalised communities as dangerous. As he accepted his party's nomination during the Republican National Convention, Trump declared, "The goal of cancel culture is to make decent Americans live in fear of being fired, expelled, shamed, humiliated and driven from society as we know it."

This is a classic example of communicative inversion deployed by the far-right, turning the status quo into a victim of resistance from the historically oppressed margins.

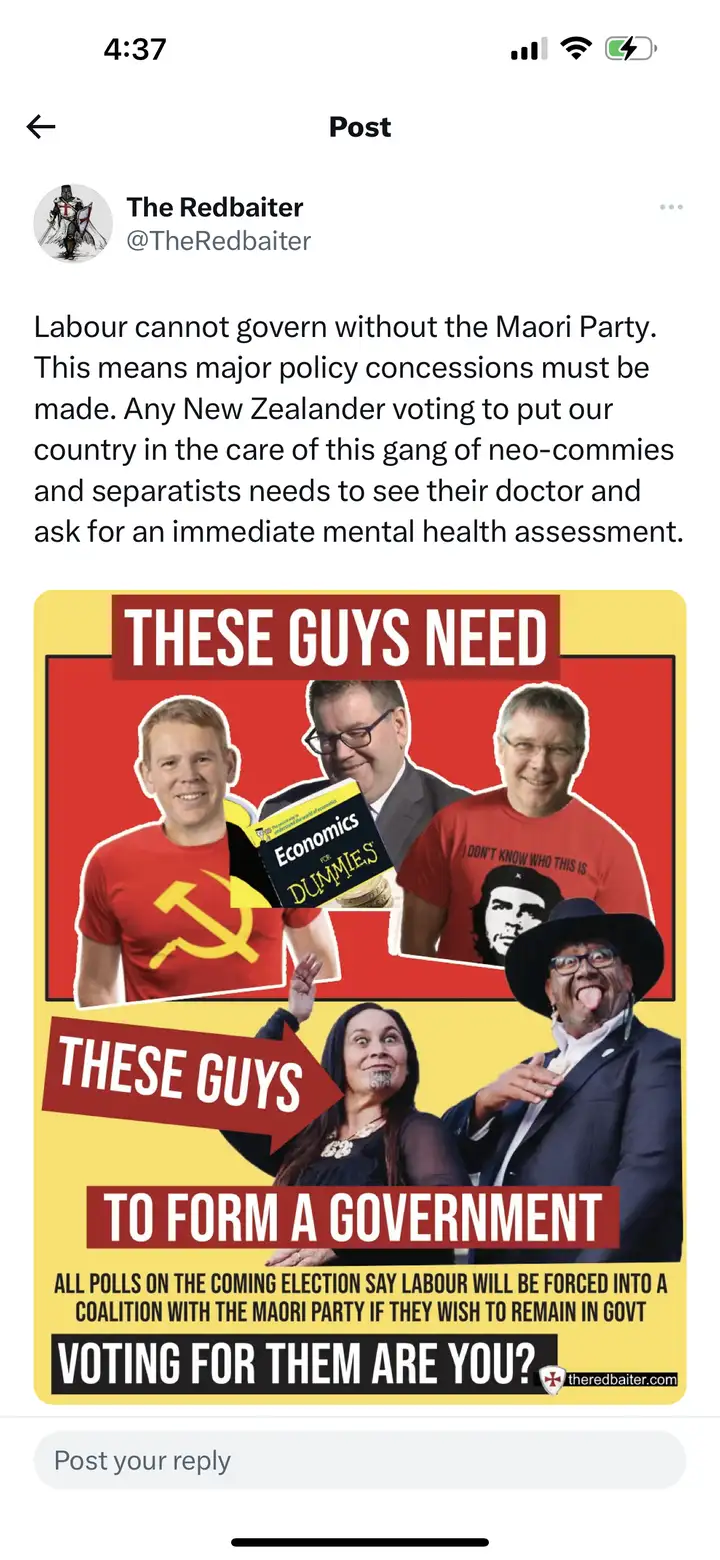

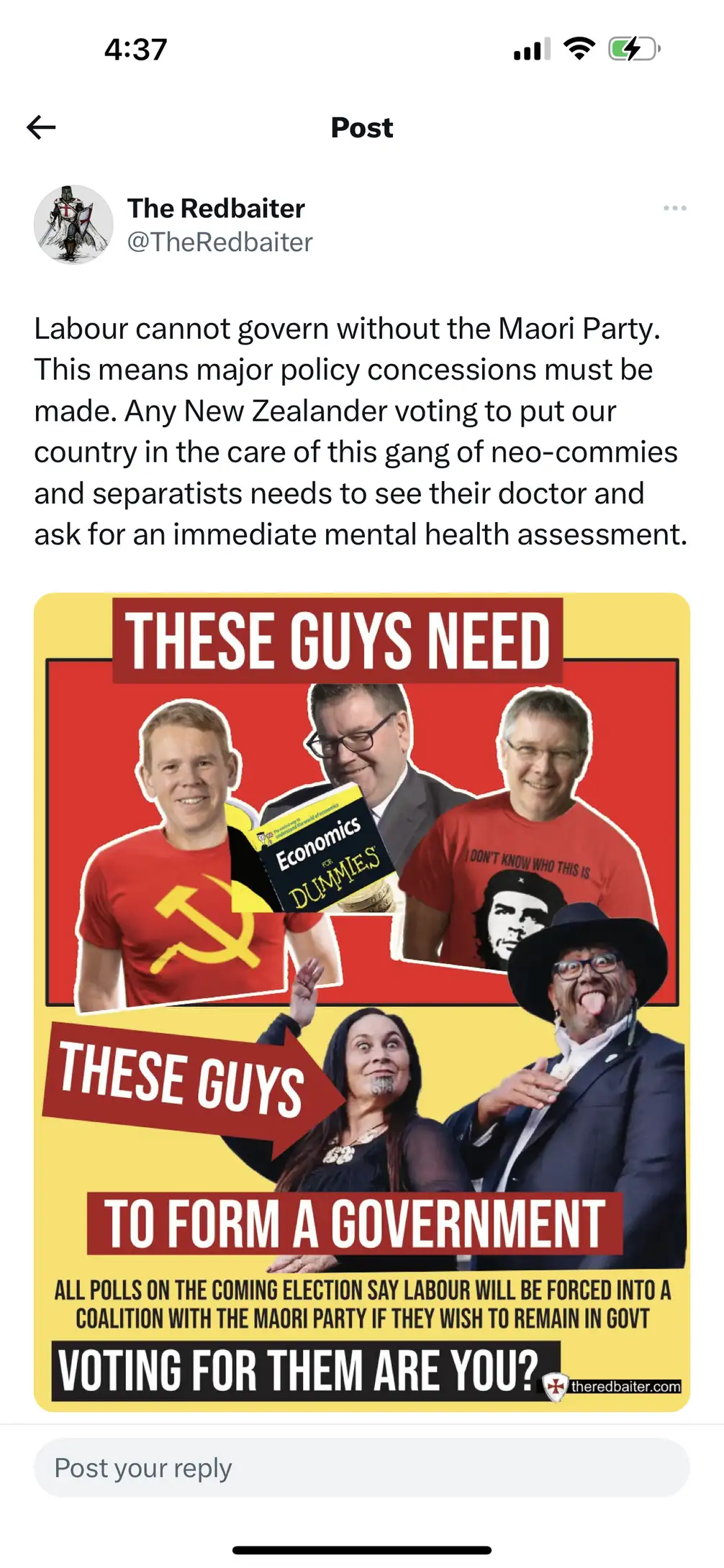

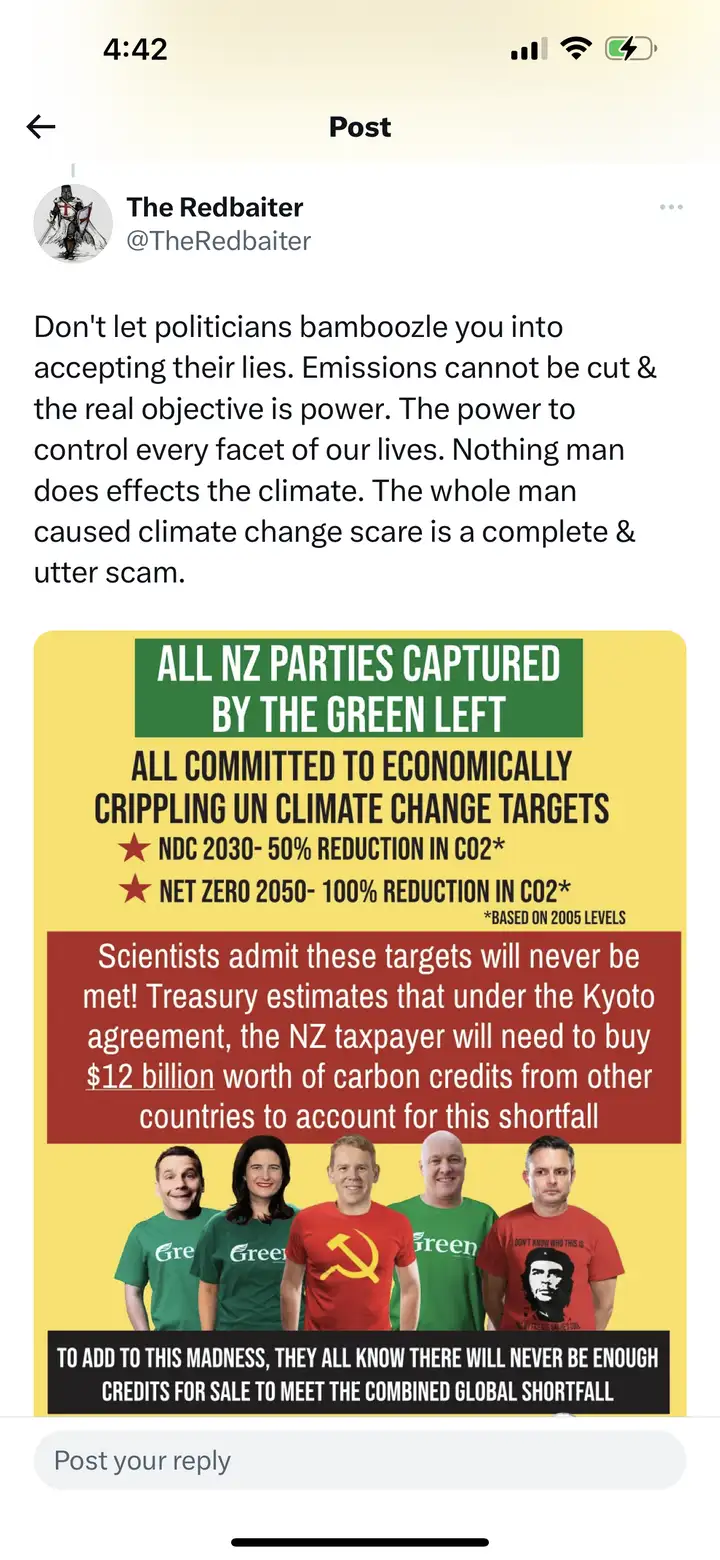

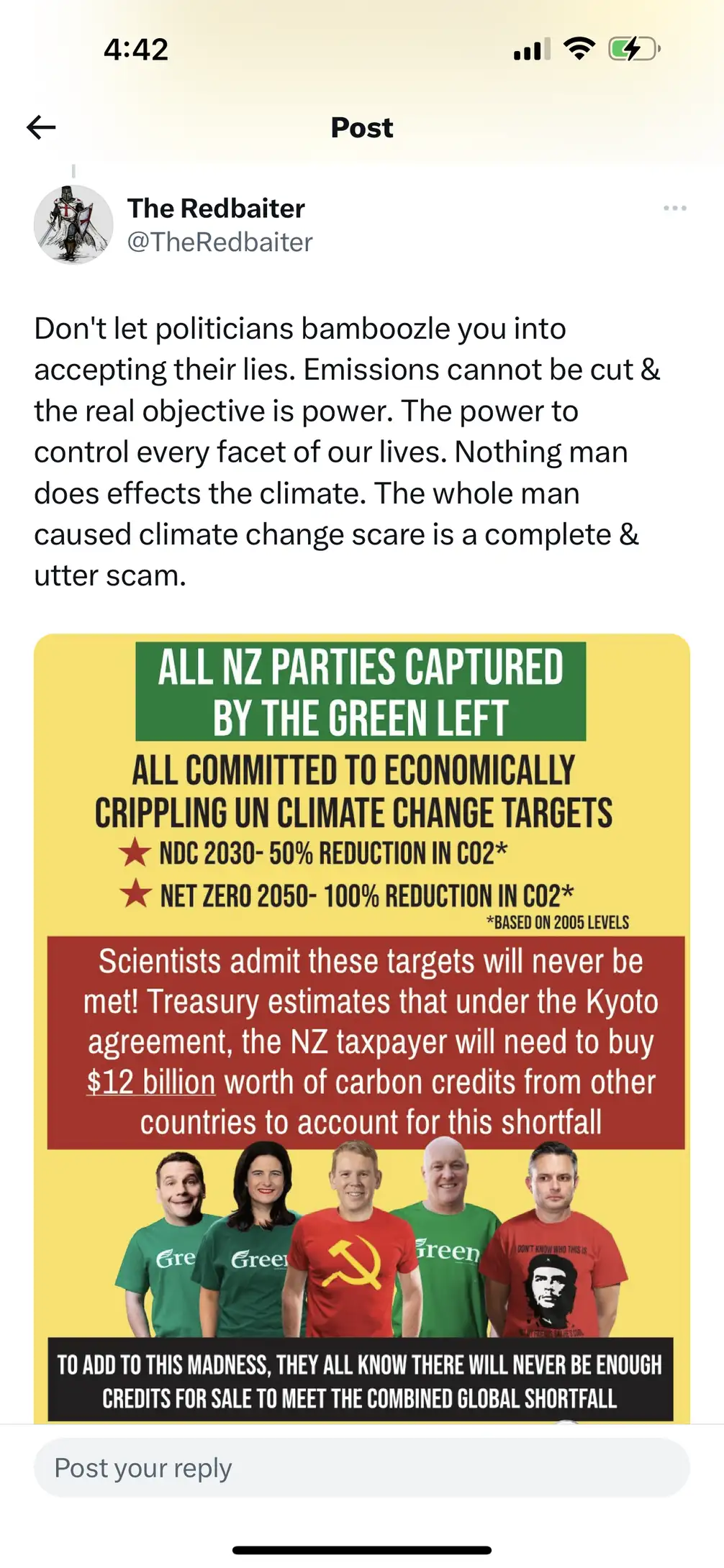

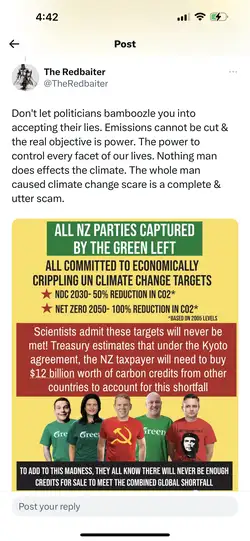

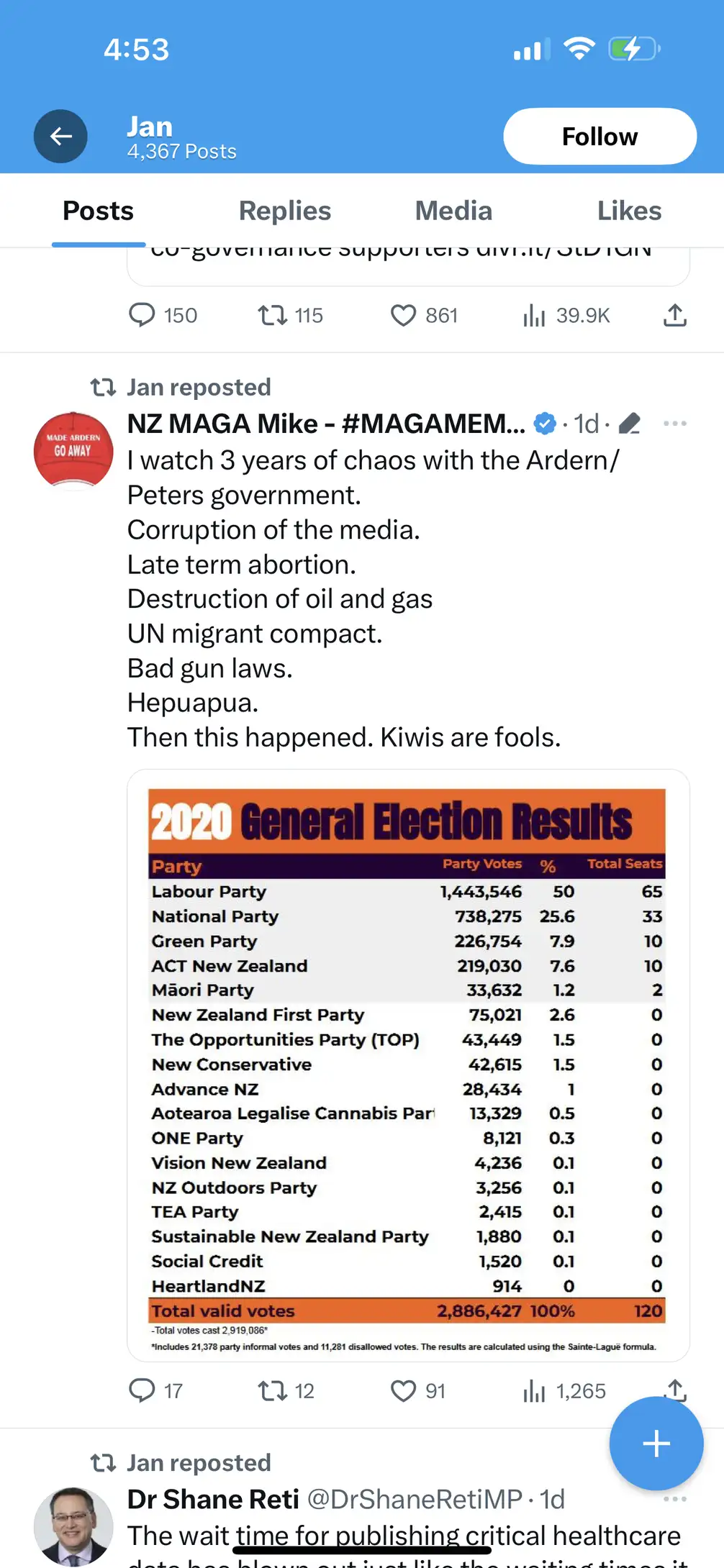

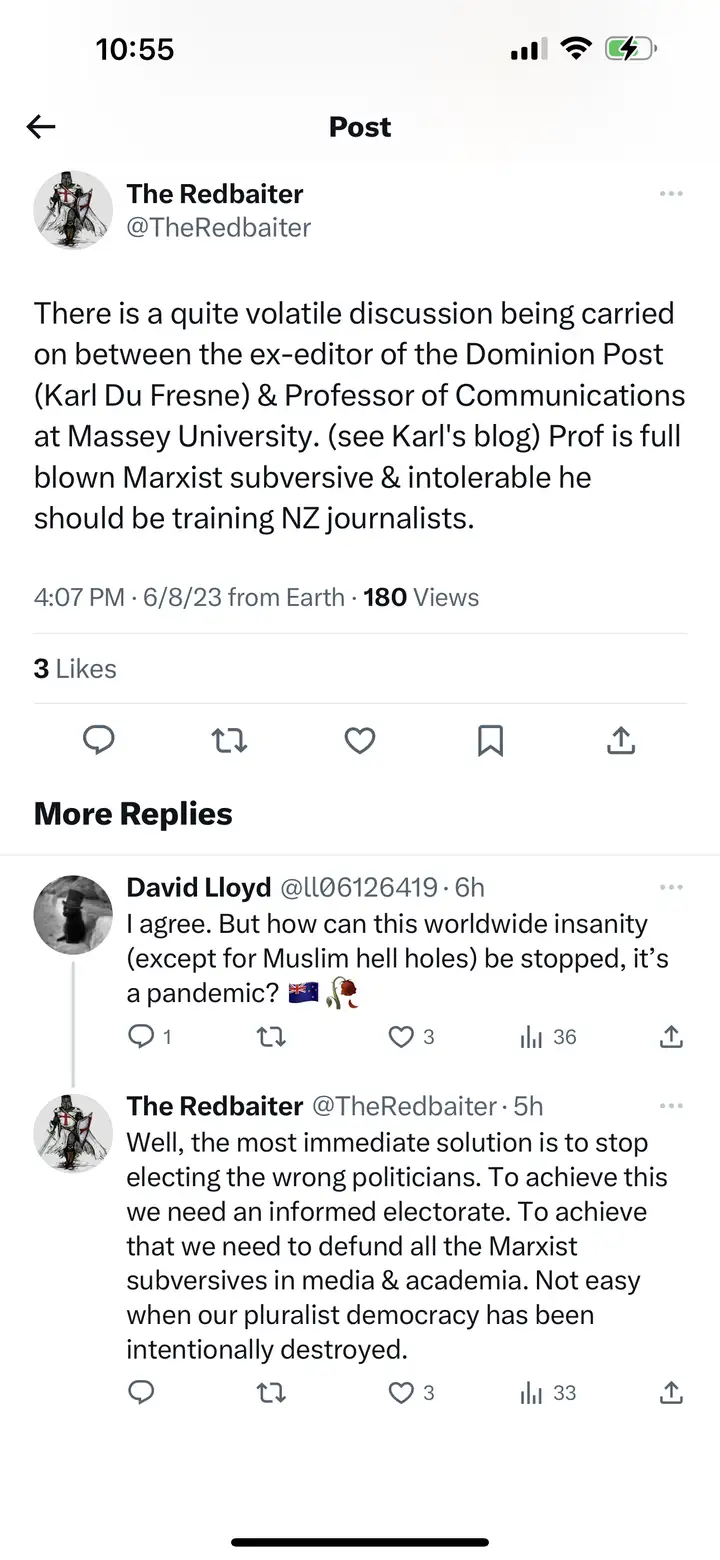

This narrative flow is well reflected in how du Fresne's targeted attacks are picked up by the far-right network, weaving in conspiracies with hate.

What these far-right mobilisations around cancel culture have in common is their organising to silence voices from the margins who are targeted by white supremacist hate, communicatively inverted as "free speech." On a variety of platforms, the far-right's hate infrastructures attack Māori, Pacific, migrant (including refugees), transgender, and Muslim activists, labelling these activists as dangerous and mobilising violence directed at them.

When the margins speak, the status quo (white, settler colonial, cisnormative, patriarchal) is threatened, and it is this status quo that the far-right seeks to hold intact. Mobilising around this status quo offers rich electoral dividends for right-wing political parties and the funders that uphold the political economy of hate.

Critical literacy is a core resource in empowering communities to identify misinformation, to challenge it, and in that process, counter the discourses that produce fear, a key organising tool of the far-right.

The rhetoric of fear that du Fresne circulates to target communication and media studies departments exists alongside his free speech advocacy for hate groups such as Family First and far-right white supremacist extremists such as Lauren Southern and Stefan Molyneux. In this vision, hate speech is unchecked while the infrastructures to cultivate capacities for critical literacies to critique and challenge the hate speech are dismantled. An ideal ground for white supremacists to flourish.

Facts too much, Mr du Fresne?

The attack on communication and media studies is based on a caricature:

"It was no accident that the emergence of these courses coincided with the long march through the institutions by which radical academics, hostile to democratic capitalism, have sought for several decades to subvert the established social and economic order. Communications and media studies provided an ideal incubator for their agenda because no empirical foundation was necessary. Academicians were free to make it up as they went along because what they taught was based almost entirely on theory."

The tried and tested red scare is recycled, reducing communication and media studies to a monolith, without empirical evidence to back up this claim.

Du Fresne is wrong. Much of the ongoing scholarship and pedagogy are shaped by the ideology of democratic capitalism, although there are paradigmatic challenges to this dominant framework and the discipline continues to witness robust inter-paradigmatic debates. Communication and media studies is a dynamic discipline, one where ideas are seriously contested and debated upon. For a journalist-turned-blogger who laments the loss of journalistic objectivity, I say, "Do your research."

His historic account of the discipline is equally incorrect because the disciplinary origins and growth in the Cold War decades are directly shaped by the project of liberal capitalism.

He then offers the absurd description that communication and media studies academics "freely make it up" as they go, wrongly assuming what is taught in the discipline is based "almost entirely on theory." For a large portion of the discipline, theory building is shaped by empiricism, and there are diverse paradigmatic approaches to the question of the relationship between data and theory.

The rant ends with nostalgia for journalism practice, free from the diktats of the university:

"One ruinous consequence is that the training of journalists has been subjected to academic capture. Not all journalism courses are taught by universities, but the threshold for entry to the profession has been progressively raised to the point where a degree, if not mandatory, is at least highly desirable. That brings budding journalists into the orbit of lecturers who are, in many cases, proselytisers for the neo-Marxist far Left."

This paragraph gives away the source of du Fresne's angst, wanting to hold on to a past that’s long gone. Before I turn to journalism education, let's note that preparing students to be journalists is a small part of what the discipline does. Communication degrees prepare students for a wide range of jobs that include communication design, advertising copywriting, media planning, production management, digital strategy, brand management, human resource management, risk and crisis management, and policy analyst, to name a few.

Why journalism schools are important?

Since my first piece appeared, a number of communication and media studies colleagues have reached out and shared their stories of being targeted by du Fresne and the far-right ecosystem (including The Platform that carried the original opinion that I critiqued) with similar targeted campaigns.

When he launched a similar uninformed attack on my Massey colleagues Dr Craig Prichard and Dr Sean Phelan, Dr Phelan, in his eloquent analysis, schooled du Fresne, writing:

"Now, I’m not sure what the rest of you make of this [i.e. du Fresne's suggestion that most people would find Sean's ideas "obnoxious" and "peculiar"], and, unlike du Fresne, I won’t claim to speak for you. But I’m pretty confident that most newspaper readers would be open-minded enough to realise that we may as well close down our universities now if they had to comply with the repressive dictates of people like du Fresne. His reaction is essentially that of a scared child, who lashes out at anything that is different from their perception of ‘normal’.

"The irony here is that du Fresne’s denunciation of me was in response to my suggestion that there is an intellectually repressive element in the New Zealand journalism culture. There’s hardly any need to make a counter-argument, therefore, since he himself does such a superb job of re-illustrating my argument."

In a peer-reviewed article, Dr Phelan offered a theoretical lens (that dirty word again!) to analyse the fiasco.

He has similarly targeted Victoria University colleague Dr Michael Daubs for his public presentation of his work on misinformation. Dr Daubs was harassed during this public event. Du Fresne frames that harassment with a both-sides trope:

"I thought his talk was both laughable and contemptible. It’s hard to imagine a more vivid example of the leftist elite’s contempt for any opinions other than its own and its determination to demonise the expression of legitimate dissent."

Note how casually du Fresne discards the evidence-based argument about misinformation as "elite's contempt for any opinions other than its own" and "its determination to demonise the expression of legitimate dissent."

He then goes on:

"He talked about “the truth” and “false stories”. He used these terms as if their meaning is settled. But who defines what’s true and what’s false? Why, people like Daubs, of course. Under the pretense of protecting us, he and others of his ilk want to control what we can say, and by extension what we think. The purpose is to extinguish all and any opinion that stands in the way of their radical, transformational agenda."

Note here the deliberate production of doubt, a classic strategy for spreading misinformation, communicatively inverting empirically-based research on misinformation as extinguishing opinion (ironic for a journalist who accuses woke journalism education of being devoid of empiricism). Attend to the conspiracy web that frames misinformation researchers as conspiracists. The attack on Dr Daubs and the Disinformation Project peaks with the following statement:

"It made me wonder just who the real conspiracy theorists are. Is it the far-right, or are the real conspiracy theorists people like Daubs and the shadowy Disinformation Project, which feverishly promotes moral panic over phantasms of its own creation?"

In this warped universe of communicative inversions, disinformation researchers become conspiracists with a shadowy agenda of subverting democracy. Contrary to the propaganda spun by du Fresne, the scientific evidence on strategies for countering conspiracy theories points to the importance of critical education and analysis, with a focus on prevention. One of the recommendations made by an international team of scientists I had an opportunity to collaborate with on managing the COVID-19 transition documented the critical role of anticipating and managing misinformation.

Here's du Fresne’s prescription for journalism education:

"There is little about the theory and principles of journalism that can’t be taught in a six-month Polytechnic course. The rest comes with experience. Generations learned it by doing, and served their readers (sorry, “consumers of content”) well."

He sees the practice of journalism as hampered by theoretical preparation for critical thought and analysis. This is elucidated well in another post that appears on the platform of the New Zealand Center for Political Research in 2021:

"Objectivity in journalism is fashionably denounced as a myth, thereby giving reporters license to decide what their readers should know and what should be kept from them. The worthy idea that journalists could hold strong personal opinions about political and economic issues but show no trace of them in their work, which used to be fundamental, has been jettisoned."

So what precisely is the challenge to objectivity in journalism as he sees it? Attacking the guidelines for the application to the Public Interest Journalism Fund, du Fresne makes it clear:

“All applicants must show a “clear and obvious” commitment to the Treaty and te reo; no exceptions.”

“Another of the guidelines (drawn up by New Zealand on Air, which is administering the fund) requires that applicants must “seek to inform and engage the public about issues that affect a person’s right to flourish within our society and impact on society’s ability to fully support its citizens”. Insofar as this gibberish can be interpreted as meaning anything at all, it suggests a leaning towards activist journalism that seeks to improve the status of disadvantaged groups. Identity politics, in other words. This interpretation seems to be supported by a further suggestion – no, let’s call it a very unsubtle hint – that applicants are likely to be regarded favourably if their journalism proposals “meet the definition of Maori and iwi journalism” or “report from perspectives including Pacific, pan-Asian, women, youth, children, persons with disabilities [and] other ethnic communities.”

This warped interpretation of the tenets of journalism committed to equity and inclusion frames journalism that seeks to improve the conditions of historically marginalised groups as activist, and therefore, not objective. What du Fresne takes issue with is the attention to Te Tiriti and inclusion of Māori journalism. Note here the empirical evidence in the scholarly literature that documents anti-Māori themes in New Zealand journalism (and you wonder why the far-right has problems with social science!).

He writes elsewhere:

"Unfortunately such people are now outnumbered by university-educated social justice activists posing as journalists who consider it their mission to correct the thinking of their ignorant, bigoted or misguided readers. This would be marginally more tolerable if they could write, but many of them can’t."

The archaic notion of journalism as the pursuit of objectivity (as if objectivity is defined outside of values and politics) is placed at odds with journalism in the pursuit of justice. For du Fresne, university education prepares students to ask questions of social justice and bring these questions into their journalistic practice, and this is a danger to journalism. This gives away his idea of objectivity in journalism, one that upholds and perpetuates the status quo, and doesn't interrogate the power and control that perpetuate it.

As Dr Phelan notes, du Fresne does an excellent job of (unintentionally) illustrating the value of robust journalism education. Fortunately, global trends in journalism have long moved far beyond the silly binaries du Fresne spins. Journalism education is here to stay and grow! Academic research is going to continue documenting the biases and erasures in journalism practice, and drawing on that to educate students toward inclusive and decolonising journalism practice.

How a communication and media studies education prepares you!

After graduating with a Bachelor of Technology (Honours) in Agricultural Engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur (the IITs has produced leading tech entrepreneurs and top leaders in global tech including Sundar Pichai at Google and Arvind Krishna at IBM), I pursued a degree in communication studies because I saw the value communication offered to building effective engineering solutions to address the needs of communities.

I am not alone in making such a career switch. You will see in communication many such career transitions, including engineers going on to study communication, with a desire to solving societal challenges.

I am proud of my PhD from the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota. The University of Minnesota has educated excellent journalists such as Michelle Norris, host of All Things Considered, National Public Radio's longest-running news service programme in the US. Norris has been nominated four times for the Pulitzer Prize and has received numerous awards for her work, including the 1989 Livingston Award, an Emmy, and Peabody Award for her contribution to ABC's coverage of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Another J-School alum was Eric Sevareid, who worked with Edward R. Murrow on CBS radio, and went on to become a commentator on the CBS Evening News for thirteen years, being recognised with Emmy and Peabody Awards.

Other significant journalists with journalism degrees include the pioneer of investigative journalism, Carl Bernstein, University of Maryland (think Watergate); Emmy and Peabody-winning journalist Connie Chung: University of Maryland; famed sportscaster Bob Costas: Syracuse University, and Pulitzer-winning, former Editor-in-Chief of the Wall Street Journal Matt Murray: Northwestern University, to name a few. This is a tiny fraction of journalism graduates who have gone on to become award-winning journalists.

In Aotearoa, the widely respected journalist Kim Hill has a degree in French and German from Massey and Otago Universities and then studied journalism at the University of Canterbury's Postgraduate School of Journalism.

Globally, as journalism responds to a rapidly transforming digital context, journalism schools are the go-to places for the education of the next generation of journalists. Fortunately, Aotearoa has rapidly caught up with this global trend.

I am humbled to teach in a School with a strong journalism programme at Massey University accredited by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications (ACEJMC) and located within a programme that is consistently ranked first in Aotearoa New Zealand. ACEJMC is the main global accreditation body of journalism education, and this speaks volumes for our excellent programme. Ours is New Zealand's longest-running journalism qualification. Our graduates are highly sought after, with 85 per cent securing employment within six months of graduation.

Journalism education, and more broadly, communication and media studies education are here to thrive. Communication research and teaching are the best antidotes to the far-right’s fringe cancel culture and its attempts to seed disorder by co-creating voices infrastructures in partnership with marginalised communities. Our research partnerships and students will continue to build justice-based communication solutions for sustainable futures, tackling the sustainable development challenges of zero poverty; no hunger; good health; good education; gender equality; reduced inequalities; sustainable cities and communities; climate action; and peace and justice etcetera.

Professor Mohan Dutta is Dean's Chair Professor of Communication. He is the Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), developing culturally-centered, community-based projects of social change, advocacy, and activism that articulate health as a human right. He is a member of the board of the International Communication Association.

Related news

Opinion: The far-right, misinformation, and academic freedom

By Professor Mohan Dutta

Opinion: The far-right's attack on communication and media studies

By Professor Mohan Dutta

Opinion: A response to Dr Chris Wilson’s review of Byron Clark’s ‘Fear’: the limits of academic expertise

By Professor Mohan Dutta.

Opinion: The right-wing version of academic freedom and communicative inversions

By Professor Mohan Dutta