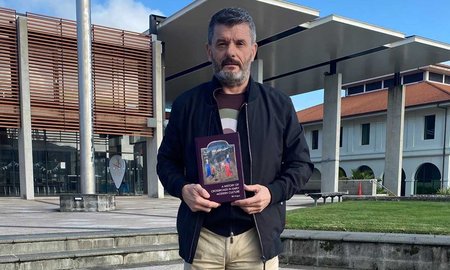

Mirjana Moffat.

As science history researcher Mirjana Moffat sat out the Covid pandemic in New Zealand, she cast her mind back 600 years to the ancient Croatian city of Dubrovnik, where the first regulated quarantine was introduced to combat the black plague.

A former Massey School of Humanities staff member and Croatian by birth, Ms Moffat is currently studying for her Master of Science Communication at the University of Otago while also taking a postgraduate history paper at Massey.

A trip back to Croatia last year gave her the opportunity to visit Dubrovnik and research original documents dating from the plague era in the 14th century. The results were presented in a seminar in March as part of the 2023 History of Medicine and Science Lecture Series conducted by the University of Otago.

“I was in Dubrovnik on 27 July, the 645th anniversary of the proclamation of quarantine in 1377,” she says.

“In the 14th century doctors believed that the plague was caused by corrupted air. Their only treatment was the advice to ‘Fuge cito, longe et tarde revertere’ – in other words flee as fast and as far as you can and take your time coming back.”

Dubrovnik had already suffered several devastating waves of the plague between 1348 and 1374, the year when Venice started restricting who could enter its port. In 1377, Dubrovnik took the unprecedented step of introducing the first trentina, 30 days of mandatory isolation, later increased to 40 days.

Enshrined in the lawbook Liber Viridis, the decree began with the words “Veniens de locis pestiferisnon intret ragusium vel districtum" – people coming from infected areas should not enter Ragusa (as Dubrovnik was known) or its surrounding land.

“Such people couldn’t enter the city until they had purified themselves for one month. Two small ships watched out for incoming vessels. They had to wait out the month at unpopulated islands. People coming from the continent were confined on the Dance peninsula," Ms Moffat says.

After three disease-ridden decades, the republic’s Great Council decided on 27 July 1377 to establish a quarantine system. It was the first of its kind in the world. Lawbook Liber Viridis (‘Green Book’) contains the quarantine decree.

In 1390, Rome was ravaged by the plague. The Dubrovnik government responded by appointing its first plague officers known as caxamorti or kacamorti in Croatian - literally 'catchers of death'. Three nobles were assigned the job of managing the quarantine, controlling entry to Dubrovnik, assigning the trentina and gathering information from travellers about plague outbreaks elsewhere. The number of caxamorti was later increased as circumstances required.

“Anyone arriving from Rome was isolated on an island, in a wooden hut. In later years there was better housing – for example in 1397 the Benedictine monastery on the island of Mljet was transformed into a quarantine facility.”

The caxamorti oversaw quarantine staff – gravediggers, cleaners, priests and surgeons.

“One of the symptoms of the plague was its short incubation period. You could be dead in a matter of hours. The authorities realised that people who survived the plague were protected from getting it again. That meant they could employ women plague survivors to act as cleaners. They also knew that clothing and merchandise could be contaminated with the plague and dangerous to touch, so incoming goods were quarantined as well as the people. There was a belief that exposure to the wind and the sun helped to cleanse goods from the plague.”

The 30-day quarantine and the social cohesion around its implementation were crucial in allowing Dubrovnik to continue to a degree the trade on which its citizens depended for their livelihood.

“The relationship between the citizens and the government was very important. There was mutual trust and they worked together," Ms Moffat says.

Six centuries later, in the spring of 2020, Croatia implemented one of the most stringent sets of anti-Covid measures in the world.

“Reading about it made me realise that when we were in lockdown in Dunedin we had our garden and the beach nearby. For me it was a time to be with family and to behave as normally as possible."

Her long-term plan is to combine her interest in science communication and in history into creating compelling stories. In 2022, Ms Moffat gave her first lecture in the History of Medicine and Science Lecture Series, based around her internship assessing the University of Otago’s Monro historical collection of anatomical books and manuscripts.

Spanning 150 years, this remarkable collection was put together by three generations of professors and chairs in anatomy at the University of Edinburgh - Alexander Monro Primus, Secundus and Tertius - and dispatched in 1871 to surgeon and politician Sir David Monro in New Zealand. In 1929 the collection was transferred to the University of Otago.

“I love the history of medicine and this kind of research. My history paper at Massey is really helping me to develop my work in science communication by ensuring I apply adequate historiographic methods in my research. Senior Lecturer Dr Karen Jillings and Professor Michael Belgrave have both helped me and given me a lot of advice.”

Ms Moffat’s next lecture, on Sir David Monro, will be in October.

“For next year I have been offered two more lecture slots. I am interested in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, so I’m planning on looking at Florence in the Medici period. For the second one I’ll choose either early Renaissance anatomy or I’ll look closer to home to Otago University.”

You can see two of Ms Moffat's lectures here:

Related news

New book explores the history and literature of crossroads

A History of Crossroads in Early Modern Culture tells the story of how physical crossroads have in history been culturally vital sites where human, demonic and divine forces were felt to converge.