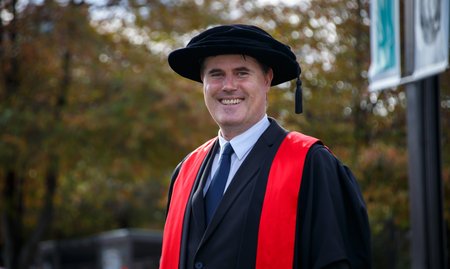

Growing up in York in the United Kingdom, a career researching marine wildlife wasn’t the most obvious choice given the city is landlocked. That changed after an OE in Aotearoa, when he settled in Kaikōura and encountered the region’s extraordinary marine life. The experience prompted him to enrol at Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University and pursue research that would directly contribute to conservation.

Dr Hall’s doctoral work represents a significant step forward for a species that has been somewhat overlooked in threat research and population monitoring.

“For most of the country, we haven’t had contemporary, reliable data on kekeno distribution and numbers, which makes it hard to assess threats. My aim was to provide data for key populations and examine the threats currently facing them. It’s my hope that this research will encourage more regular data collection and population safeguarding in the future,” Dr Hall says.

Updating national population numbers

The first part of his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) focused on updating kekeno population estimates nationwide through modelling, supported by data shared by fellow researchers, Department of Conservation (DOC) rangers and tourism operators. Alongside this national update, Dr Hall carried out field work at two key sites - Kaikōura, where no assessment had been completed since the 2016 earthquake, and Banks Peninsula, which hadn’t been surveyed in two decades – to generate new, on-the-ground population data to feed into the wider model.

Dr Hall says the fieldwork involved a lot of physicality.

“Some colonies required long hikes in and out and full days working hands-on with the animals. We assessed the body condition of pups and non-permanently marked them to estimate colony sizes. It was an amazing experience and a privilege to work so closely with these incredible animals. Each field season was super rewarding, knowing the data would help conserve the species.”

Photo credit: Dr Alasdair Hall, captured from afar and cropped in. Keep your distance from kekeno for their safety and yours.

Turning research into conservation action

The second part of his PhD examined threats facing kekeno. In Kaikōura, State Highway 1 runs close to the colonies; in Banks Peninsula, oil spill risk is heightened due to proximity to a major harbour and cruise vessel traffic.

“In both cases, the aim was to better understand the threat, then look at practical ways to mitigate it by working with partners on the ground.”

There proved to be a slight issue, given that seals accessing a major highway proved globally unusual. With no previous seal research to draw on, Dr Hall adopted methods normally used for land mammals and applied them to kekeno. His work showed that kekeno were reaching the road at very specific sites, which had shifted as road infrastructure changed after the 2016 earthquake. Pups were over-represented in road mortality data which led to a targeted solution.

“We were able to suggest a specific road guard rail type to help prevent kekeno getting on the road, and worked with DOC, mana whenua and Waka Kotahi to implement the rails in the worst areas,” Dr Hall says.

“Since their installation in April 2024, preliminary results show road mortality has substantially declined where barriers were implemented, and the same barriers are now being implemented elsewhere in the country.”

Photo credit: Dr Alasdair Hall, captured from afar and cropped in. Keep your distance from kekeno for their safety and yours.

A resilient and crucial species

Through the research, Dr Hall developed a deep appreciation for the resilience of kekeno, especially those in Kaikōura.

“After the Kaikōura earthquake, much of the main colony at Ōhau Point was covered in landslip debris, animals were killed, the coastline changed dramatically, and the highway was rebuilt closer to the ocean, reducing the colony depth. Despite that, we found that in 2023, the number of pups was almost identical to 2015, and kekeno had begun breeding more linearly along the coast in response.”

Dr Hall hopes his work encourages consistent monitoring of the species nationwide.

“This isn’t just important for management and conservation, but they’re a sentinel species. They give us insight into the health of their local marine ecosystem, from climate change impacts to emerging diseases affecting multiple species.”

Continuing the work

Dr Hall credits his supervisors, Professor Louise Chilvers and Dr Jody Weir, with helping shape the direction of his research.

“They challenged me to make the PhD my own and gave me huge support through the inevitable learning curve of doing a PhD. I’d also like to thank my partner, mum and brother for their support and encouragement, and the many volunteers who put in long hours, often in times in tough conditions, to help collect the field data.”

Now based in Wellington, Dr Hall works as a research contractor on a range of kekeno-related projects, both in the field and through data analysis. He hopes to continue working with marine species, having discovered how much he enjoys the research process.

His advice for others considering similar doctoral work is to get out into the field as much as you can.

“You learn invaluable skills, not just hands-on techniques, but things like finding accommodation, budgeting and planning work programmes, which help when looking for jobs. Make connections with other candidates, faculty, researchers, and staff from regional and local councils and organisations. They have so much knowledge that can improve the quality of your research and those relationships are helpful when it comes to finding opportunities and support post-PhD.”

Photo credit: Dr Alasdair Hall, captured from afar and cropped in. Keep your distance from kekeno for their safety and yours.

Related news

Nowhere to hide: "Forever chemicals" unavoidable for dolphins and whales

New research reveals the significant risk New Zealand’s toothed whales and dolphins (odontocetes) face from human-made per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). These are also known as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down naturally in the environment.

Technology reveals the hidden world of an endangered subantarctic penguin population

Dr Chris Muller’s PhD research saw him living on an isolated subantarctic island and developing new drone technology to gain insight into one of the world’s rarest and most endangered penguin species.

Sea lion colony confirmed, but work still needed

While celebrating the Department of Conservation's announcement of a New Zealand sea lion (rāpoka) breeding colony on Stewart Island, a Massey University marine mammal specialist is calling for further action to protect the endangered species.