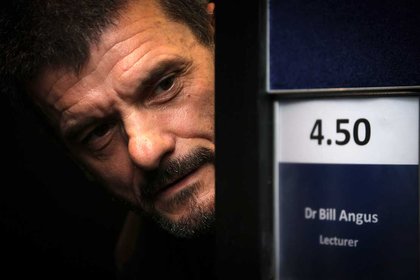

Shakespeare scholar Dr Bill Angus tracks the role of spies and informers in the Bard's work and society.

Citizens of the 21st century are well used to mass surveillance of the cyber variety, but a new book exposes just how prevalent spies and informers were in Shakespeare’s life and lines.

Massey University Shakespeare scholar Dr Bill Angus explores the role of spies and informers in the scripts and society of the Bard and his contemporaries.

His research reveals how playwriting in 14th and 15th century England could be a risky business – with the threat of mutilation or death – in a society riddled with the Crown’s informers and spies.

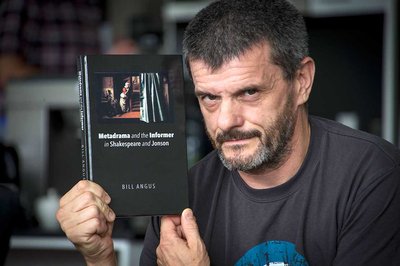

The catalyst for Metadrama and the Informer in Shakespeare and Jonson (Edinburgh University Press, 2017) was reading plays by Shakespeare’s contemporaries. “Something was going on in their society to suggest that people on stage should be watching what other people on stage are doing or overhearing.

“Whether it be someone standing behind a hedge and passing information on, or watching from behind a curtain like Hamlet’s Polonius, most plays of the era have some recognition of this narrative device and structure,“ says Dr Angus, a senior lecturer in the School of English and Media Studies based at the Manawatū campus.

He wondered if there was something more historical to explain why this was such a recurring feature of theatre at the time, and it occurred to him that Elizabethan society of Shakespeare and his peers was, in fact, full of informers.

“Everybody was looking over everybody else’s shoulder. A lot of the literature of the time is about how awful informers were and how you might not be able to talk in public without somebody overhearing you.

“There is a heightened consciousness at this time of the dangers of even casual conversation,” Dr Angus says.

Gathering information by spying or eavesdropping was a lucrative line of work, fostering an atmosphere of suspicion and fear and creating an insidious backdrop for authors, who harnessed the theme for theatrical purposes.

People were paid to overlook or oversee all kinds of commercial and civic activities, including unloading of a ship at the docks to ensure it was properly processed by customs, Dr Angus says.

“The rewards for informing were potentially huge – there were a number of acts throughout 15th century that codified how much you were supposed to be paid. If you were an informer who informed on a ship that had not been properly processed you might be entitled to half of the ship’s value.”

Paid informers and spies were lurking everywhere in Elizabethan England, Dr Bill Angus' book reveals.

Spies handsomely rewarded

Gathering information by spying or eavesdropping was a lucrative line of work, fostering an atmosphere of suspicion and fear and creating an insidious backdrop for authors, who harnessed the theme for theatrical purposes.

People were paid to overlook or oversee all kinds of commercial and civic activities, including unloading of a ship at the docks to ensure it was properly processed by customs, Dr Angus says.

“The rewards for informing were potentially huge – there were a number of acts throughout 15th century that codified how much you were supposed to be paid. If you were an informer who informed on a ship that had not been properly processed you might be entitled to half of the ship’s value.”

New understandings of links between life and art in Dr Bill Angus' new book.

Paid informers made writing life risky

His research connects the presence of informers in Elizabethan theatre with their prevalence in real life and; “confirms suspicions in the field that something more than mere artistic experimentation is going on in metadrama [the play within the play].

“The real physical dangers inherent in early modern dramatic authorship have been underplayed at times,” he says.

“As far as we know, none of the principal dramatists of the metropolis was punished by mutilation, their ears or noses cut, but other writers were not so lucky. In 1579 John Stubbs and his publisher, William Page, were imprisoned and had their right hands hacked off for distributing The Discovery of a Gaping Gulf where into England is like to be Swallowed, which dared to address the question of the Queen’s marriage,” he writes in the introductory chapter.

Dramatists suffered though, he says. “Thomas Kyd, perhaps the most celebrated playwright of his time, died at 35 after being informed upon, arrested and viciously racked over things he had allegedly written.”

Through analysing the use of metadrama, he brings a fresh focus for understanding and decoding the often, poisonous presence and influence of spies and informers off-stage. In the theatre, spies and informers were cast in: “simple self-reference, role play about role play, plays within plays, or audiences watching audiences,” he explains.

Dr Angus’ book – being launched this Friday at the Palmerston North City Library at 6pm – is the first by a Massey University scholar on William Shakespeare (1564-1616), whose 37 plays and 154 sonnets are widely celebrated, performed and critiqued worldwide and in many languages, with dozens of books and articles published every week.