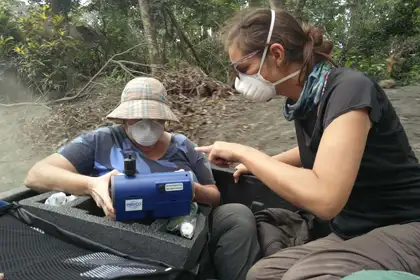

Carol Stewart (left) with Susanna Jenkins (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) testing ash samples in Ambae, Vanuatu, in 2018, as part of an international team assessing volcanic impacts from the Ambae eruptions. (Credit Graham Leonard)

In addition to her role in the School of Health Sciences, Dr Stewart is a researcher with the Resilience to Nature’s Challenges National Science Challenge, co-director of the International Volcanic Health Hazard Network (IVHHN) and member of the New Zealand Volcanic Science Advisory Panel (NZVSAP). Her specialty is determining the health hazards of volcanic ash and she has been involved in the responses to numerous international eruptions, the recent eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai in Tonga.

“Ash from every eruption is different, so each time you’ve got to go in and analyse it,” Dr Stewart explains.

“The most important characteristic is the grain size distribution. The finer the grains are on the ground, the higher the potential for them to be picked up by wind and breathed deep into the lungs.”

While ash coarser than 0.1mm diameter quickly drops out of the air and is unlikely to be inhaled, ash between 0.1 and 0.01mm diameter will deposit in the eyes, nose and throat, causing irritation and a cough. Ash particles finer than 0.01mm diameter travel deeper into the lungs, worsening the symptoms of people with existing lung problems, potentially making it difficult to breathe.

Many people also worry about the contamination of food and water supplies. However, in Dr Stewart’s experience, this risk is much further down the list.

“The biggest risk of all is having no water, because then all the sanitation consequences become a lot worse. The next thing to worry about is the microbiological safety of the water; you’ve got to make sure people have a means of treating it. Then, thirdly, you can start worrying about the chemical composition of the water.”

Fortunately, chemicals leaching out of volcanic ash usually affect water’s taste long before reaching toxic concentrations, and even then, short term exposure is unlikely to do serious harm. However, there are exceptions.

“You’ve always got to be aware that you might get some really freaky ash composition which doesn’t make water taste nasty but may be quite toxic.”

While the benefits of having an ash sample to analyse are clear, advice is often needed long before such analyses can be performed.

“It’s really hard because getting an ash sample is not a priority for anyone else except us [scientists]. In the early days of messaging there’s always a real tension between getting something out rapidly with incomplete information, versus waiting for better information that may come too late.”

Carol Stewart doing fieldwork in Tanna, Vanuatu.

After the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption on 15 January, Dr Stewart was approached by Tongan community leaders here in New Zealand who wanted simple, practical advice about precautionary measures that could be taken by their friends and family back home. Dr Stewart and her colleagues at the University of Canterbury, GNS Science and NIWA prepared messages that were translated into Tongan by community leader Emeline Afeaki-Mafile’o and then turned into an infographic by Massey University design student Matt Luani. Associate Professor Siautu Alefiao of Massey University’s Niupatch organised for one thousand fliers to be printed and added to aid boxes being sent to Tonga.

“It only took about three or four days, it was really fast,” Dr Stewart says.

On 22 January, an all-important ash sample arrived, collected by the New Zealand Defence Force from beside the runway during their delivery of aid supplies.

“It was not the most pristine looking sample I’ve ever seen…but we all got to work on that.”

Within 48 hours the team had produced a peer-reviewed report on the grainsize distribution, with chemical analyses reported a few days later.

“It turned out that the ash was actually not acidic, which is really unusual. It was also very low in fluoride, which was a big relief because fluoride is one of the main concerns.”

With Ruapehu currently showing signs of renewed activity, and numerous other active volcanoes on and around our shores, there’s sure to be more volcanic eruptions in Aotearoa New Zealand in future. When that time comes, Dr Stewart and the teams at IVHHN and NZVSAP will be ready.

“It’s really nice to be useful in a crisis like this,” reflects Dr Stewart. “And Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai was an amazing chance to rehearse our systems.”

This article was first published by Resilience Challenge, authored by Jenny Stein.

More news

Zinc link might make roof water safer to drink

A new study of Wellington roof catchment rainwater has found that zinc in galvanised steel roofs can kill some bugs. But households concerned about the safety of emergency roof catchment rainwater in the event of an earthquake still need to disinfect it before drinking it.

Massey researcher investigates the most lethal volcanic phenomena on earth

Over the past decade, Associate Professor Gert Lube has been at the forefront of the development of new volcanic hazards models.

New Zealand’s communication of volcanic risk under the spotlight

New ground-breaking research could drive fundamental changes to the way New Zealand agencies communicate and respond to volcanic risk.