Thomas Nash.

New Zealand’s Climate Minister James Shaw has said that climate change is not an environmental problem, it’s an economic problem with environmental effects.

Shaw’s point is that the drivers of environmental degradation are at their heart economic drivers and that if you want to stop the degradation, you need to change those economic drivers. There’s a notable if little noticed example of this framing in the debate happening right now in education circles about the emerging moniker for humanities and social sciences: SHAPE (Social Sciences, Humanities and the Arts for People and the Economy). The SHAPE acronym is designed to be to the arts what STEM has been to the sciences. A rebranding and collective identity building exercise, if you will. While STEM (Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics) is now well established as a concept, SHAPE is not and, in true arts and humanities style, it has generated a debate about its own meaning.

The British Academy describes SHAPE as Social Sciences, Humanities and the Arts for People and the Economy. There’s a live debate though as to whether SHAPE should instead be Social Sciences, Humanities and the Arts for People and the Environment.

It could be a good thing to have a catchy new term for arts, humanities and social science, as long as it catches on. It could also be a good thing to be having a debate about the meaning of that term. But here are two reasons why replacing the word “economy” with the word “environment” would be a mistake.

First because retaining the word economy helps to embed economics as a social science, whose basic tenets are shaped by our social conversation and, in many cases, are highly contested. This is important because some economists assert that their particular economic theory - let’s say free market capitalism - is some kind of scientific truth rather than simply a prevailing conventional orthodoxy. Understanding that our existing economic system is of our making is an important first step to being able to remake this system in a way that serves all people fairly and that is consistent with our climate and environmental imperatives.

Second because, as discussed above, there is no point in trying to solve our environmental problems without fundamentally shifting our economic settings. The drivers of environmental degradation are economic drivers. Around 70 per cent of global emissions are produced by 100 corporations. Those corporations are shaping and responding to the economic conditions that make their activities profitable. So are the producers of agricultural emissions and freshwater pollution in New Zealand.

If we were to situate our economy within the planetary boundaries that are required to maintain a safe climate, clean water, clean air and flourishing biodiversity for example, commercial activities that overshoot those boundaries would no longer be profitable and would stop. These ideas have been laid out by economist Kate Raworth, drawing on work by environmental scientist Johan Rockström. Others frame this through the concept of “externalities” - the notion that there are factors like climate or water pollution, which, if properly and fairly taken into account by a provider of goods or services, would change what gets provided to us in the market.

It’s easy to see why people would like to anchor the environment within this emerging educational term for the study of arts and social sciences. We should be serving people and the environment. The trouble is that for too long economics and the economy have been allowed to exist on their own out there, unbridled by concern about people or the environment. The more we talk about economics in all our fields of education, the more we democratise the study of our economy and the more chance we will have to change the way it runs.

Because, just like society, the economy is all of us and all of our work and daily activities. The economy is not just the companies on the stock exchange, the Chamber of Commerce and the business confidence index. The economy is every piece of unpaid work that parents - mostly women - do every day. The economy is every unrecognised public service provided by councils and government agencies to give people an opportunity to live healthy and fulfilling lives. The economy is every Marae-based organisation providing essential services and building community in areas not served by public services. The economy is every social enterprise providing goods and services that advance and regenerate our society and our environment, rather than extract from them.

The more we inject the study of humanities and arts into the economy, the more we might begin to reclaim our economy from a concept that mainly serves the interests of those who already hold wealth and who use it to increase their power and position in the world. This collective exercise of reclaiming our economy is of fundamental importance to the cause of environmental and climate justice.

When we characterise SHAPE as social sciences, humanities and the arts for people and the economy then we give ourselves a better chance to redesign that economy in a way that flows from what people are learning and teaching in these fields. This gives us a better chance to build a new economy that is more social, more human and more in tune with the great tapestry of human history and understanding that the arts have woven together over millennia. Perhaps the most sensible outcome here is for this new catch-all term for the arts to become social sciences, humanities and the arts for people, the economy and the environment. That framing would put the environment at the centre of our work in the humanities, without abdicating our responsibility to humanise the economy.

Thomas Nash is Social Entrepreneur-in-Residence at Massey University’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Related news

Disarmament campaigner in social entrepreneur role

Disarmament activist Thomas Nash been appointed the first Social Entrepreneur-in-Residence for the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Massey University.

Making sense of an uncertain world: lecture series

China's influence, Auckland's superdiversity, philosophical issues in health and science research, the transformative power of theatre, music, literature - just a few of the sizzling topics in this year's Our Changing World public lectures by Massey University humanities and social science scholars.

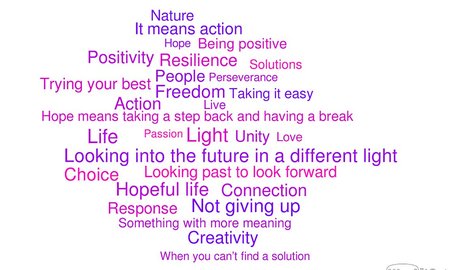

Teaching young people hope

What gives you hope? That is the question He Kaupapa Tūmanako/Project Hope, a course developed by Massey sociologists, has been asking secondary school students.