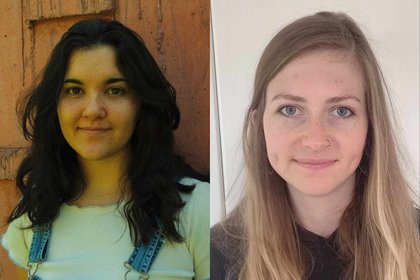

Andrea Mansell (left) and Skyler Goument are both helping to fill a knowledge gap in international research with their honours research.

Andrea Mansell is undertaking qualitative research for her Bachelor of Science (Honours) into the problems autistic graduates have in finding a suitable job. Fellow student Skyler Goument is researching the work experiences of autistic teachers for her honours in psychology.

Based on international data, it’s estimated that between one to two per cent of the Aotearoa New Zealand population, between 50,000 to 100,000 people, are autistic.

Sourced via online autism forums, all four of Andrea’s research participants were diagnosed as autistic at an early age.

“They always knew they were different. They experienced similar upbringings, being stigmatised, bullied at school and feeling socially excluded. Autistic people have difficulty socialising with other people, maintaining eye contact, understanding body language – difficulties that neurotypical people don’t have," she says.

Now in their mid-twenties, the participants all struggled to find a job in their chosen field, despite having excelled at university in competitive degrees like software engineering and microbiology.

“Only one succeeded in getting a job, and that was because they had help from their family. The others really struggled. They only attended job interviews once or twice because they felt they were being judged."

“At university it was possible for them to establish simple, structured routines that made the experience of studying manageable. They just didn’t know what to do after graduation. Some spent months at home doing nothing, overwhelmed at the thought of having to cope with change.”

Andrea says her participants all lacked self-esteem and all believed neurotypical people were a better fit for the workforce.

“They felt they had to try to mask their autism in interviews. They found the whole experience frightening. One participant told me, "The way they looked at me I knew there was stigma. They looked at me with judging eyes and pity"."

Andrea's research points to the need for helping autistic graduates prepare for entering the workforce. Her study concludes that they need support with job interview skills, social skills, navigating change and strengthening independence and self-confidence.

As the microbiology major told her, "I was taught in university how to be a microbiologist and I was taught all the things I should know as a microbiologist, but no one taught me how to start working as a microbiologist".

The research suggests that employers need to move beyond social-based interviews to consider performance and the job context. For example, some of the autistic graduates could have been applying for jobs in laboratories, where they might not need extensive social skills.

Research has shown that approximately 40 per cent of children with autism will go on to study in tertiary education. As the rate of autism diagnoses in school students rises, honours student Skyler Goument says it’s important that autistic children feel included at school and able to connect with a diversity of teachers.

Her research focuses on the lived experience of autistic teachers in mainstream schools, a subject which has received little international attention to date.

“Two of my four participants were clinically diagnosed – one in his early 40s and the other at 14 – while the two women were self-diagnosed in their 20s. All of them had a tough time at school themselves, struggling to make friends and slotting into peer groups. They got into trouble at school; a lot of misunderstandings with teachers. And they experience the same misunderstanding with staff members now, working as a teacher.”

Given their own schooling experience, all four participants felt they had a special connection to students who were themselves neurodivergent. Their insight into what it was like to be autistic meant they were able to be a supportive mentor figure in these students’ lives. This also extended to neurodivergent students with ADHD.

Skyler quotes one participant, who told her, “This little boy came up to me and he was just talking about space and going on and on, obviously a special interest, and then he’s like, thank you so much for listening to me. Everyone else ignores me and tells me to go away".

Another participant recalled teaching an autistic student who was seen by other teachers as difficult to deal with in the classroom.

The participant said, “I didn’t (find him difficult) at all. He really enjoyed being in my class…it was calm because he knew what was going on, because everything was very well set out, because all the lessons were designed in a way that we all knew what was happening and how. But he also would follow me around when I was on duty everywhere. I used to spend the whole time chatting with him and it was just natural. And I think he gravitated towards me as well in a way. It was probably because I was similar to him, it’s probably because our brains were working in a similar way".

The social and organisational aspects of being a teacher – working with other staff, being in the busy, noisy school environment, attending staff and parent-teacher meetings – were problematic and exhausting for all the participants. Autistic teachers are not well provided for in schools.

Skyler says the modern open-plan learning environment where four or five classrooms might be in the same room poses both a challenge and a threat to neurodivergent teachers and students.

Her participants did note improvements in the way inclusiveness is supported in schools today compared with their own school years. But her research points to the need for more training for neurotypical teachers in understanding autistic students (and teachers) and how they think.

School of Psychology Lecturer Dr Sharon Crooks says the work of her two honours students is important, especially given how little research has been done to date.

“We know that up to 80 per cent of autistic people are without work, so the unemployment rate is disproportionately high. The research that Skyler and Andrea are undertaking will shed further light on the aspirations as well as the work experiences of autistic people within the New Zealand context," Dr Crooks says.

Related news

Postgraduate student passionate about neurodiversity awareness

Jess Goodman is passionate about creating a sense of community for Massey's neurodivergent students.

Opinion: Initiatives to support neurodivergent students and staff

By Dr Kathryn McGuigan.

Supporting neurodiverse students

Academics in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences have been working to identify the challenges neurodiverse students may encounter, and ways to support them during their time at university.