Dr Boroughs explains that if someone identifies as bisexual, there can be pressure to be either gay/lesbian or heterosexual.

Research shows that bisexual people experience health outcomes that are worse than gay, lesbian or heterosexual people, says visiting scholar and honorary research fellow Associate Professor Michael Boroughs.

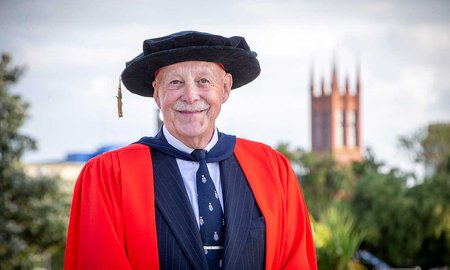

An Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology at Canada’s University of Windsor, Dr Boroughs plans to spend his year on sabbatical at Massey University collaborating with faculty to conduct studies on health issues faced by bisexual people in Aotearoa New Zealand.

He explains that if someone identifies as bisexual, there can be pressure to be either gay/lesbian or heterosexual.

"They’re vulnerable to stigma from heterosexual people who might say well, if you like people of the same gender, why don’t you just do that, while gay or lesbian people might say the same thing – if you’re gay or lesbian, why don’t you just say that?

“So there’s a dichotomy that’s being forced upon non-monosexual people to be monosexual.”

Dr Boroughs and his host and research collaborator Senior Lecturer Dr Ilana Seager van Dyk from the School of Psychology, will conduct focus groups across New Zealand to explore health issues faced by bisexual people. Based on the data collected from these groups, they plan to develop a set of questions to create a new psychological tool that may be used in research or clinical settings.

Dr Boroughs estimates that sexual minorities: gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, takatāpui and ‘mostly heterosexual’ people, form upwards of 30 per cent of the population.

“Stigma and bullying are certainly faced by gay and lesbian people and also heterosexual people who come from minority racial, ethnic, or religious backgrounds.

“But what I find so compelling is that based on the literature, there’s something about the stigmatisation of bisexual, or other non-monosexual people, that is linked to poorer health outcomes, mental or physical.”

Dr Boroughs and Dr Seager van Dyk.

Dr Boroughs’ research and clinical work focuses on the mental health of adolescents and emerging adults in the areas of bullying, physical appearance, trauma, mood and anxiety disorders, substance use and sexual health.

“One of the things that I am passionate about as I pivot towards researching bisexual people is that they are a substantial part of the population,” he says.

“There are more bisexual and non-monosexual people than all gay and lesbian people put together as a percentage of the population. It’s important that we explore the question of health outcomes more in a clinical and research context so that these groups within the sexual minority population are getting adequate and evidence-based health services provided to them.”

Dr Boroughs says he would like to see patients that present in a physical or mental health setting being asked questions about their sexual orientation, including looking at health risks and screening for those more vulnerable to traumatic stress, bullying and childhood sexual abuse among other issues.

“It starts at the first point of contact, about learning and showing acceptance for people when they are reporting a minority sexual orientation. Health providers may be more aware of issues that affect a gay or lesbian patient, but less so about those issues that uniquely affect bisexual people.”

Dr Boroughs says that he has found in the research that if young people in schools are being bullied, including about their sexual orientation, for example, having identified themselves to their peers as bisexual, the health outcomes are ‘staggering’.

“People who are bullied at school experience a chronic stressor and trauma. Studies show there are morphological changes in the brain and also that victims of bullying are vulnerable to increased risk for coronary heart disease in adulthood.

“The negative outcomes to physical and mental health linked with being bullied at school have been described as a public health crisis, and I would agree with that.”

Dr Boroughs says that when he was running focus groups on being bullied among sexual minority emerging adult men a decade ago, most participants did not make a connection between having been bullied and their current state of health.

That is now changing, he says. In his recent work, university students seeking psychological services are more likely to report bullying as a significant development trauma that affects them in a negative way.

“One of my students has just completed her master’s thesis on the relationship between being bullied at school and going on as a young adult to have physical appearance issues and concerns with body image such as excessive exercise, eating disorders and symptoms of Body Dysmorphic Disorder,” he says.

Dr Boroughs says cognitive behavioural therapies are effective and can be very helpful in dealing with depression, anxiety and other problems linked with being bullied, but he would also like to see more research into prevention-interventions to stop bullying in schools and prevent problems from arising in the first place.

He looks forward to seeing how things are done in New Zealand.

“One of the pivots I’ll be making in my own lab in Canada when I return home is to incorporate aboriginal and indigenous approaches to research but also to focus more specifically on bisexual and other non-monosexual people.”

Related news

Clinical psychologist aims to understand Rainbow folks’ high rates of mental health concerns

Senior lecturer in clinical psychology Dr Ilana Seager van Dyk’s ultimate goal is to better understand the vast mental health disparities experienced by LGBTQ+ youth, and to improve evidence-based clinical care for these youth and their families.

Gay men’s health and discrimination researcher awarded

Massey University alumnus and health psychologist Professor Michael Ross has been awarded a Doctor of Science for his lifetime of research into sexual risk behaviour and mental health in gay and bisexual men across cultures and continents.